August 11, 2008

The Hidden Zero Effect

Choose:

$5 today or $10 in a year.

Picking $5 is called temporal discounting-- you pick a sooner-but-smaller outcome simply because it is sooner.

But it's more than a preference based on how soon you get paid. If the question is changed:

$5 in 7 years, or $10 in 8 years

Then you can feel the pull to choose the $10-- even though the $5 is still one year earlier than the $10. So it's not simply people prefer sooner over later. It's also how far away the payoffs are. How soon is sooner? At some point in the future, your choices flip.

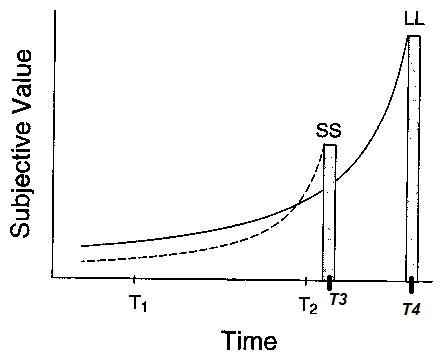

In fact, this is predictable (reliably so in animals)-- and follows a hyperbolic function:

Imagine there is a smaller-sooner reward at time T3, and a larger- later one at a time T4. At a very distant, early time T1, you prefer the solid line (the larger-later reward), because they are both far enough away that the time delay seems insignificant.

But if you choose at a close time T2, the choice has flipped and you prefer the smaller reward, because it seems sooner. The closer "soon" is, the more you're willing to settle. Hyperbolically.

II.

Why does this happen?

It's behaviorism. The effect of rewards are temporally dependent. Try it on your kid.

How this phenomenon is described is important, and it is frequently backwards. You don't prefer sooner choices that are smaller, but if they are both far enough away you'll choose the larger choice; you choose the larger choice all the time except if the choice is asked of you close to payoff.

If you intuitively know your future is long, and real, you don't succumb to it as much. But if the future is an abstraction, then you begin to discount your choices.

The future is real only if you are real, i.e. your identity is fixed. If your identity is in flux-- whether from personality disorder, bipolar, being a teenager, going through a divorce-- if there are different "yous" all the time, you cannot make decisions based on the future. If "you" aren't going to be the same in the future, how can you make decisions about it?

In other words, temporal discounting is not exactly an error; it is an accurate reading of the likelihood of change of one's identity.

III.

So how do you resist this?

One way is to make explicit the hidden zero:

Choose $5 today and $0 in a year, or $10 in a year and $0 today.

That hidden zero seems obvious, and it is obvious cognitively, but not instinctively. These habits and "errors" are hard wired in us because they are protective-- eat while you can, jackals are coming.

But they don't help when you're opting into a 401(k): "Choose $13,000 today and $0 at retirement, or $0 today and $13,000 at retirement."

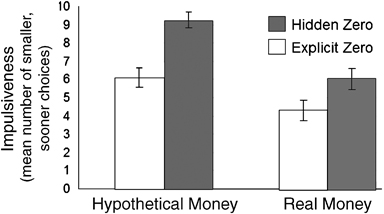

When you make the hidden zero explicit, people choose differently-- less impulsively:

Whether it's real or hypothetical money, people choose sooner-but-smaller less often when they are told about the $0.

When dealing with impulsive people, or people whose identity is in flux, it is important to make explicit all parts of a choice, because time has little meaning.

IV.

But what caught my attention about this is the difference between real and hypothetical money. Why does making it real money significantly reduce the number of sooner-but-smaller choices, whether or not the zero is explicit? If anything, seeing the money on the table might drive them to choose the sooner (but smaller) choice-- the instinct becomes real ("eat now.")

The experiment was to ask subjects 15 questions of the form "$X today, or $Y in a month." But a second group of people, the "Real Money" group, were told that one of these hypothetical choices would randomly be used to pay them real money at the end of the questionnaire.

Do you see the problem? The subject isn't making a choice between a sooner payoff vs. a later payoff, but between sooner payoffs vs. all the other sooner payoffs, and later payoffs vs. all the other later payoffs.

$6 now, or $12 in a month----- he chooses $6.

$8 now vs. $10 in four days---- he chooses $10.

But now he's told one of these choices, randomly, will be paid to him. So instead he picks:

$6 now vs. $12 in a month--- he chooses $12

$8 now vs. $10 in four days-- he chooses $10

Because in the first pair, he would have been paid either $6 now or $10 in four days. "No way, I'm not risking losing $10 in four days just to get $6 now. In order to risk losing $10 in four days, I need a bigger payment down the road. The only choice available to me is $12, so I'll take it." Get it?

Aggregate 15 such choices and it's no surprise people pick larger-later payoffs more often. The real way to do this would be to offer the people real money for every single choice they made, but that didn't happen here.

Unfortunately, it doesn't happen in real life, either. Most of the time, people make decisions based on hypothetical scenarios, with a faint expectation that perhaps one of these decisions will result in an actual payoff. When people with identity issues are presented with a series of binary choices, we expect them to consider them independently, and we often marvel at how bad their choices seem to be. But they may be taking a series of binary choices and inappropriately pooling them to maximize an overall outcome.

That's why we get frustrated with their choices. We can't understand why they made that choice because the reason has to do with an entirely different decision that should be unrelated but to them is linked.

And so it becomes important to restate things into independent, binary choices. Certainly life choices are affected by other life choices, but for those floundering in their own identities, things need to become more concrete, not less.

When dealing with impulsive people, or people whose identity is in flux, it is important to make explicit all parts of a choice, because time has little meaning.

IV.

But what caught my attention about this is the difference between real and hypothetical money. Why does making it real money significantly reduce the number of sooner-but-smaller choices, whether or not the zero is explicit? If anything, seeing the money on the table might drive them to choose the sooner (but smaller) choice-- the instinct becomes real ("eat now.")

The experiment was to ask subjects 15 questions of the form "$X today, or $Y in a month." But a second group of people, the "Real Money" group, were told that one of these hypothetical choices would randomly be used to pay them real money at the end of the questionnaire.

Do you see the problem? The subject isn't making a choice between a sooner payoff vs. a later payoff, but between sooner payoffs vs. all the other sooner payoffs, and later payoffs vs. all the other later payoffs.

Immediate rewards ranged from $2 to $8, delayed rewards ranged from $5.40 to $8.70, and delays ranged from 7 to 140 days.In effect, this stops becoming a temporal discounting problem and becomes a game theory problem. He's maximizing the sooner payoffs, the later payoffs, and then also temporally discounting. E.g.,

$6 now, or $12 in a month----- he chooses $6.

$8 now vs. $10 in four days---- he chooses $10.

But now he's told one of these choices, randomly, will be paid to him. So instead he picks:

$6 now vs. $12 in a month--- he chooses $12

$8 now vs. $10 in four days-- he chooses $10

Because in the first pair, he would have been paid either $6 now or $10 in four days. "No way, I'm not risking losing $10 in four days just to get $6 now. In order to risk losing $10 in four days, I need a bigger payment down the road. The only choice available to me is $12, so I'll take it." Get it?

Aggregate 15 such choices and it's no surprise people pick larger-later payoffs more often. The real way to do this would be to offer the people real money for every single choice they made, but that didn't happen here.

Unfortunately, it doesn't happen in real life, either. Most of the time, people make decisions based on hypothetical scenarios, with a faint expectation that perhaps one of these decisions will result in an actual payoff. When people with identity issues are presented with a series of binary choices, we expect them to consider them independently, and we often marvel at how bad their choices seem to be. But they may be taking a series of binary choices and inappropriately pooling them to maximize an overall outcome.

That's why we get frustrated with their choices. We can't understand why they made that choice because the reason has to do with an entirely different decision that should be unrelated but to them is linked.

And so it becomes important to restate things into independent, binary choices. Certainly life choices are affected by other life choices, but for those floundering in their own identities, things need to become more concrete, not less.

19 Comments