February 1, 2010

4 Easy Steps Towards Weight Loss That Aren't Drugs, Diets, Or Excersise

I can't tell you not to eat it, but I can tell you how

If you don't like boring science, just skip to section III for the answer.

I.

Type II diabetics- and everyone else-- have two problems with their diets. First, eating too many calories causes weight gain. Second, food (like carbs) that causes excessive or prolonged insulin secretion, while helpful in the immediate (it clears the sugar so you aren't hyperglycemic) over time leads to insulin tolerance and resistance.

Hence, low carb diets are favored for both weight loss and for keeping insulin levels low(er).

However, while carbs are potent stimulators of insulin, protein and fat contribute as well. For example, consider two meals each of 2000kJ and 40g of carbohydrate:

Meal 1: steak and potatoes

Meal 2: bread, peanut butter, and milk

Not only is the insulin secretion not the same, it isn't even close: Meal 1 induces only half the insulin response of meal 2.

An old study measured the insulin response to some foods, relative to white bread (=100.) It also measured glycemic score, (e.g. per 1000kJ of it, not per 100g of it.)

You can see that the insulin response is not always related to the glycemic score. For example, brown rice is "as bad" as white bread (same glycemic score), yet causes considerably less insulin secretion. If you're diabetic, you'd want to eat brown rice instead of white bread. Etc.

In a more recent study, the weighted average of the insulin scores in a mixed meal was the best predictor of actual insulin levels-- carbohydrate amounts and glycemic index were not. (Fat, however, was a predictor.)

Summary: same calories, same amount of carbohydrate can result in different insulin responses.

II. How much insulin do you really need?

If I give you 100g of oral glucose vs. 100g IV glucose, will the insulin response be the same? No-- the oral glucose causes 3 times more insulin to be secreted. Think about this.

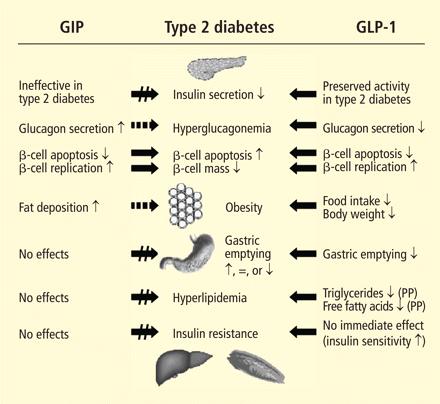

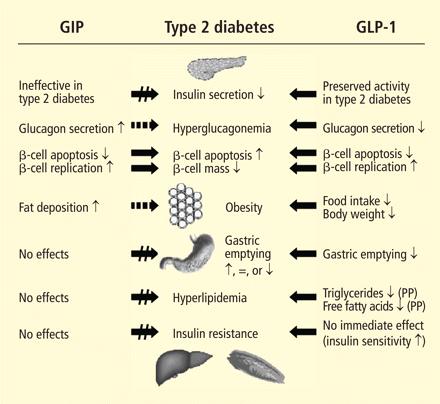

The reason is that hormones GLP-1 and GIP are secreted by the intestine within 15 minutes of eating-- specifically, after the absorption of fat and glucose there-- and are responsible for (among other things) 50%-70% of the insulin response.

The amount of insulin secreted is determined not just by the glycemic load, but the rate at which it reaches the intestine, because that's where GLP-1 and GIP will be released-- the main drivers of insulin response.

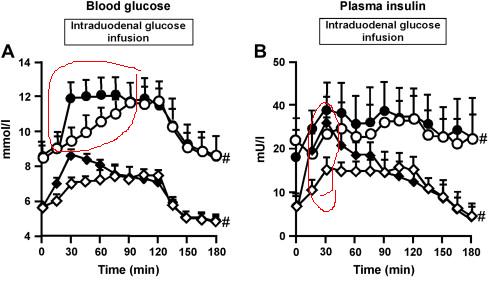

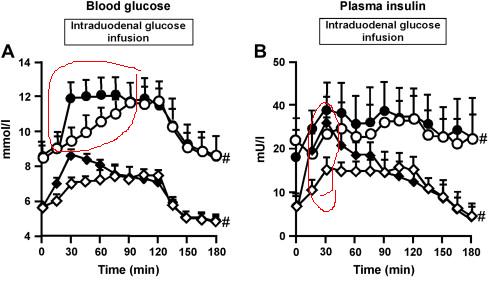

(From Aug 2009)

(From Aug 2009)

Notice that when the rate of infusion of is doubled (from 2 to 4kcal/min) the insulin must explode upwards to result in the same level of blood glucose. You don't want that: chronic high insulin leads to insulin tolerance and resistance.

But now imagine taking a fixed amount of glucose, and either:

Observe that the blood sugar is higher if you ate the sugar faster. For that meal, you were exposed to higher blood sugar. And insulin, more pronounced in the normals. For about 30 minutes, the people with the quick appetite experienced almost twice the insulin.

So slowing the rate at which glucose/food gets to the intestine would result in lower insulin levels and lower blood glucose, without necessarily changing the calories. If that sounds weird to you, learn it in the reverse: speeding up the glucose to the intestine will increase the GIP and GLP-1 and insulin response.

Eating smaller meals and less sugar clearly will help. But I think you see where I'm going:

III. Small Changes That May Help More Than A Little

Obviously, changing what you eat and how much you eat is very important. But these suggestions are not about altering the content of your chosen meal.

They're going to seem obvious now, but you should do them anyway.

1. Eating the same amount of food but much more slowly.

Any association you make to the European meal is your own business. The science says cramming the food down your throat while driving to the prison camp is a very bad idea.

2. Same amount of food, but change the order of the food you are eating.

Eating the fat and protein portion of your meal before the carbohydrate will slow gastric emptying. (It may also make you feel full and you eat less.) Don't eat extra fat and protein-- just move the protein portion to the front.

What you should not do is crack open a soda or iced tea or juice before you eat. If you must drink soda, which you mustn't, do it at the end.

If you are including a salad in your meal, definitely eat that first. (Soup would be an even better idea.)

3. Get more sleep.

Growth hormone is released during slow wave sleep, especially around 4-5am. Cortisol is inhibited. Sleep deprivation reverses this.

Even if total sleep time is the same, suppressing SWS reduces glucose tolerance. So: no sleeping pills, and get the sleep apnea handled.

Prolonged partial sleep deprivation increases ghrelin (appetite stimulating) and decreased leptin (appetite suppressing.)

4. Put cinnamon on your meal.

A bit of a cheat, but...

3g of cinnamon added to rice pudding reduced insulin levels with no effect on blood glucose. How can the body get away with using less insulin to deal with the sugar? Apparently because a) it increased GIP (see above); b) it stimulated the insulin receptor, resulting in increased glucose uptake. It should be logical, therefore, that cinnamon could exert its effect even if given separately from the meal: a small study found that 5g of cinnamon even 12h before the meal helped reduce glucose responses.

I.

Type II diabetics- and everyone else-- have two problems with their diets. First, eating too many calories causes weight gain. Second, food (like carbs) that causes excessive or prolonged insulin secretion, while helpful in the immediate (it clears the sugar so you aren't hyperglycemic) over time leads to insulin tolerance and resistance.

Hence, low carb diets are favored for both weight loss and for keeping insulin levels low(er).

However, while carbs are potent stimulators of insulin, protein and fat contribute as well. For example, consider two meals each of 2000kJ and 40g of carbohydrate:

Meal 1: steak and potatoes

Meal 2: bread, peanut butter, and milk

Not only is the insulin secretion not the same, it isn't even close: Meal 1 induces only half the insulin response of meal 2.

An old study measured the insulin response to some foods, relative to white bread (=100.) It also measured glycemic score, (e.g. per 1000kJ of it, not per 100g of it.)

You can see that the insulin response is not always related to the glycemic score. For example, brown rice is "as bad" as white bread (same glycemic score), yet causes considerably less insulin secretion. If you're diabetic, you'd want to eat brown rice instead of white bread. Etc.

In a more recent study, the weighted average of the insulin scores in a mixed meal was the best predictor of actual insulin levels-- carbohydrate amounts and glycemic index were not. (Fat, however, was a predictor.)

Summary: same calories, same amount of carbohydrate can result in different insulin responses.

II. How much insulin do you really need?

If I give you 100g of oral glucose vs. 100g IV glucose, will the insulin response be the same? No-- the oral glucose causes 3 times more insulin to be secreted. Think about this.

The reason is that hormones GLP-1 and GIP are secreted by the intestine within 15 minutes of eating-- specifically, after the absorption of fat and glucose there-- and are responsible for (among other things) 50%-70% of the insulin response.

The amount of insulin secreted is determined not just by the glycemic load, but the rate at which it reaches the intestine, because that's where GLP-1 and GIP will be released-- the main drivers of insulin response.

(From Aug 2009)

(From Aug 2009)Notice that when the rate of infusion of is doubled (from 2 to 4kcal/min) the insulin must explode upwards to result in the same level of blood glucose. You don't want that: chronic high insulin leads to insulin tolerance and resistance.

But now imagine taking a fixed amount of glucose, and either:

- closed symbols: big dump (3kcal/min for 15 min) followed by trickle (0.71kcal/min next 2 hours)

- open symbols: constant rate (of 1kcal/min x 2 hours)

Observe that the blood sugar is higher if you ate the sugar faster. For that meal, you were exposed to higher blood sugar. And insulin, more pronounced in the normals. For about 30 minutes, the people with the quick appetite experienced almost twice the insulin.

So slowing the rate at which glucose/food gets to the intestine would result in lower insulin levels and lower blood glucose, without necessarily changing the calories. If that sounds weird to you, learn it in the reverse: speeding up the glucose to the intestine will increase the GIP and GLP-1 and insulin response.

Eating smaller meals and less sugar clearly will help. But I think you see where I'm going:

III. Small Changes That May Help More Than A Little

Obviously, changing what you eat and how much you eat is very important. But these suggestions are not about altering the content of your chosen meal.

They're going to seem obvious now, but you should do them anyway.

1. Eating the same amount of food but much more slowly.

Any association you make to the European meal is your own business. The science says cramming the food down your throat while driving to the prison camp is a very bad idea.

2. Same amount of food, but change the order of the food you are eating.

Eating the fat and protein portion of your meal before the carbohydrate will slow gastric emptying. (It may also make you feel full and you eat less.) Don't eat extra fat and protein-- just move the protein portion to the front.

What you should not do is crack open a soda or iced tea or juice before you eat. If you must drink soda, which you mustn't, do it at the end.

If you are including a salad in your meal, definitely eat that first. (Soup would be an even better idea.)

3. Get more sleep.

Growth hormone is released during slow wave sleep, especially around 4-5am. Cortisol is inhibited. Sleep deprivation reverses this.

Even if total sleep time is the same, suppressing SWS reduces glucose tolerance. So: no sleeping pills, and get the sleep apnea handled.

Prolonged partial sleep deprivation increases ghrelin (appetite stimulating) and decreased leptin (appetite suppressing.)

4. Put cinnamon on your meal.

A bit of a cheat, but...

3g of cinnamon added to rice pudding reduced insulin levels with no effect on blood glucose. How can the body get away with using less insulin to deal with the sugar? Apparently because a) it increased GIP (see above); b) it stimulated the insulin receptor, resulting in increased glucose uptake. It should be logical, therefore, that cinnamon could exert its effect even if given separately from the meal: a small study found that 5g of cinnamon even 12h before the meal helped reduce glucose responses.

38 Comments