July 7, 2010

Why Parents Hate Parenting

no, i don't hate you, i just hate what I didn't become

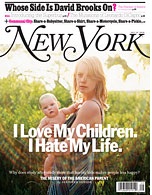

no, i don't hate you, i just hate what I didn't becomeNew York Magazine's article, All Joy And No Fun: Why Parents Hate Parenting, has 19 million pages of quotes and examples, but no answer. Too bad; the answer is right there.

Here's how the article starts:

There was a day a few weeks ago when I found my 2½-year-old son sitting on our building doorstep, waiting for me to come home. He spotted me as I was rounding the corner, and the scene that followed was one of inexpressible loveliness, right out of the movie I'd played to myself before actually having a child, with him popping out of his babysitter's arms and barreling down the street to greet me.

For the new readers, that's your sign that there's a contagion nearby, suit up. When a person sees their life as a movie, that means they're the main character and everyone else is merely supporting cast. And when one of the extras-- in this case, the kid-- goes off script, she doesn't just get upset, she has a full blown existential crisis:

I recited the rules of the house (no throwing, no hitting). He picked up another large wooden plank. I ducked. He reached for the screwdriver. The scene ended with a time-out in his crib... Two hundred and 40 seconds earlier, I'd been in a state of pair-bonded bliss; now I was guided by nerves, trawling the cabinets for alcohol. My emotional life looks a lot like this these days. I suspect it does for many parents...Wow! Her 2½-year-old acts like he's 3½, and four minutes later she's willing to settle for vanilla extract.

It is at this point, only two paragraphs in, that it should have occurred to the writer that the reason "parents are unhappy" may not have anything to do with the kids. That insight, however, most emphatically does not occur to her or anyone connected with the article.

Which is why it is accurate, though mysterious, to say that the reason parents are unhappy is these articles.

II.

To illustrate the unique unhappiness of parents, i.e. NY Magazine parents, the article describes a UCLA study in which researchers analyzed 1500 hours of video from 32 middle class families in their homes. The clip described in the article is this: a mom trying to get her 8 year old son to stop watching TV and do his homework. Ponder that.

The director of research in this study has watched this scene many times. The reason she believes it's so powerful is because it shows how painfully parents experience the pressure of making their children do their schoolwork. They seem to feel this pressure even more acutely than their children feel it themselves.

Powerful, got it? As in pay attention to this clip. You can imagine what the clip shows, we've all been there, some of us on both ends. The clip shows a struggle millions of parents can relate to.

But for that reason, it's quite ordinary. What makes it powerful?

In order to understand the real importance of this clip, forget about what actually happens in the video and focus on what people saw in the video.

This is what the writer of the article saw:

It's a weekday evening, and the mother in this videotape, a trim brunette with her hair in a bun and glasses propped up on her head, has already worked a full day and made dinner. Now she is approaching her 8-year-old son, the oldest of two, who's seated at the computer in the den, absorbed in a movie. At issue is his homework, which he still hasn't done.

No, that's not the issue, it barely receives a mention. Maybe it's the rum talking, but am I the only one who read that description of the clip and thought "the mom sounds hot?" That's the issue. The issue is that she is a trim brunette with a bun, with glasses, with a look, whose relative perfection is being marred by the time burglar in the den. The issue isn't the homework, the issue is her. Trim brunette with glasses and a bun=put together mom who has it all, so why isn't she happy?

I'm not saying that mom thinks that-- I'm saying that the writer of the article thinks that; she devoted the majority of the paragraph and almost all of her emotional energy to describing her. But it's a non-sequitor, if the point is about getting the kid to do homework, what difference does it make how she looks or what she's cooked?

It doesn't. But the writer cannot grasp this, because the main character in the movie is the mom, the story is about her. Surely, how she looks must have some importance.

I hope it requires no elaboration that had the writer chosen to see the clip as a story about a curious but bored child tormented by a descriptionless gadfly, this would have been a very different article indeed. But it wouldn't be in NY Magazine, it would be in Omni.

III.

It would be a pointless act of euthanasia to criticize the article, except that these popular press articles are more than bathroom reading, they are the template for how to think about these social issues, in the same way that you can't think about Obama without resorting to language implanted by CNN or the New York Times. Try it. It's impossible.

These articles offer you the freedom to argue about the conclusions, but trick you into accepting the form of the argument.

Here's an example. Passive readers of this article, e.g. everyone on the toilet, will feel the comparative emphasis of the description of the mom and unconsciously assume it is relevant to the thesis. You're going to read "trim brunette" and infer "put together mom" and then you're going to try to figure out why the "put together mom" is having such trouble with the entropy machine her husband gave her. Whatever conclusion you reach, the form of that conclusion will be, "the reason otherwise well put together moms are not happy is..."

From which you can derive every other insanity common to such articles, which in this case the writer does explicitly for you anyway:

One hates to invoke Scandinavia in stories about child-rearing, but.. If you are no longer fretting about spending too little time with your children after they're born (because you have a year of paid maternity leave), if you're no longer anxious about finding affordable child care once you go back to work (because the state subsidizes it), if you're no longer wondering how to pay for your children's education and health care (because they're free)--well, it stands to reason that your own mental health would improve.Because, you know, no Scandinavian women ever kill themselves at double the rate of Americans.

None of this will make you a happier parent, let alone a better one. The article itself makes the point that, "parents' dissatisfaction only grew the more money they had, even though they had the purchasing power to buy more child care." So why bring up Scandinavia? Because it jives with some other incompletely thought out political position?

These articles are cognitive parasites, that's what makes them dangerous. They change the way you think. Even if you disagreed with the conclusion, you're still going to approach this problem from, "why aren't put together moms happy?" This will never lead you to the answer.

The real form of the question, the one that generates the correct answer simply in its asking, is, "why doesn't having kids-- or getting married or getting a better job or getting laid or anything else I try to do-- make me happy? Oh. I get it. I'll shut up now."

I was sure that color coordinating the baby and the bathroom would make me happier but it didn't... should I have gone with lavender?

IV.

Two other short examples.

As per the article, fathers apparently suffer more than mothers. At first I thought it was because they were single fathers, but no, these were married ones. Not what I would have guessed, but I'm open to new information. Per the article, most arguments a couple has-- "40%"-- are about the kids.

"And that 40 percent is merely the number that was explicitly about kids, I'm guessing, right?" This is a former patient of [a couples counselor], an entrepreneur and father of two. "How many other arguments were those couples having because everyone was on a short fuse, or tired, or stressed out?" This man is very frank about the strain his children put on his marriage, especially his firstborn...This man is very frank. It took, what, 6 months of therapy? to discover that many of the arguments with his spouse are related to stress.

He may be frank, but he's obviously clueless:

...This man is very frank about the strain his children put on his marriage, especially his firstborn. "I already felt neglected," he says. "In my mind, anyway. And once we had the kid, it became so pronounced; it went from zero to negative 50. And I was like, I can deal with zero. But not negative 50."The guy was in a relationship without any kids, and he felt neglected. What the hell did he think was going to happen when he had kids? Daily oral? The article writer doesn't detect anything remarkable there, I'm guessing because she probably thinks it's not remarkable to feel neglected in a relationship.

Unfortunately, here's what the article writer does think is remarkable. This is what she wants you to understand from that interview, this is the very next sentence:

This is the brutal reality about children--they're such powerful stressors that small perforations in relationships can turn into deep fault lines.

Got it? It was all working until the kids came.

Note also the arrogance of the parents relative to the Catimini clothing models that live with them. Can you be vaguely dissatisfied, unfulfilled and possibly even resentful of your marriage, yet fake it enough that your spouse thinks you love them more than anything? So why do you think you can fool your 8 year old? Because he's 8? He smells it on you, it reeks, like sepsis. And yes, it will spread to him eventually.

Jim Gaffigan, in between jobs

Jim Gaffigan, in between jobsV.

Another example:

A psychologist offers the article's one useful insight about unhappy parents: "They become parents later in life. There's a loss of freedom, a loss of autonomy."

Ok, sounds plausible. This, however, is the article's interpretation of that insight:

It wouldn't be a particularly bold inference to say that the longer we put off having kids, the greater our expectations. "There's all this buildup--as soon as I get this done, I'm going to have a baby, and it's going to be a great reward!" says Ada Calhoun, the author of Instinctive Parenting and founding editor-in-chief of Babble, the online parenting site. "And then you're like, 'Wait, this is my reward? This nineteen-year grind?' "

The author of a parenting book still cannot help but see children as a reward, as a cherry on top of a cake, not because she is brain damaged but because for 40 years she has been told by people, like herself, like New York Magazine, that they were.

There's a word for all of this, but everyone gets queasy when I use it.

VI.

I have a surprising piece of advice for parents, which I hope will be taken in the spirit it is offered: your kid doesn't want to be around you that much. No one does. This isn't because you're a bad person but because you're an ordinary person. You are not such a unique, creative, intelligent or even interesting person that the kid benefits from constant exposure to you. When you have something to offer, maximize and concentrate that time, and then get the hell out of the way.

This advice is quite practical. Parents often don't know what to do with their kids, so they overwhelm them with their attention instead. What no parent realizes is that the vast majority of that overinvolved time is spent irritated. Add it up yourself. Nagging, bored, looking at your mobile. The obvious message is that you're not satisfied.

That's the template you've offered him.

I don't know if helicopter parenting will turn the kid into a wimp as many claim, but I do know that it will make the kid hate you. The natural individuation that will occur in adolescence is going to be a lot more severe, get ready. Of course, by that time the parents will be too emotionally exhausted to keep on helicoptering, so you get the awesome combination of a lifelong history of overcontrol, with a sudden removal of nearly all of it, exactly at the time the kid discovers meth. Well played, New York Magazine parents, well played.

---

Also: Don't Settle For The Man You Want

---

http://twitter.com/thelastpsych

147 Comments