December 31, 2010

What Does The Woman Who Feels No Fear Feel?

I'm going to need another drink

An article in Current Biology.

A 44 year old woman named SM has a rare, autosomal recessive disorder that resulted in bilateral amygdalar damage and...

On no occasion did SM exhibit fear, and she never endorsed feeling more than minimal levels of fear... SM repeatedly demonstrated an absence of overt fear manifestations and an overall impoverished experience of fear. Despite her lack of fear, SM is able to exhibit other basic emotions and experience the respective feelings. The findings support the conclusion that the human amygdala plays a pivotal role in triggering a state of fear and that the absence of such a state precludes the experience of fear itself.

If you know anything about science, you know it loves to yell at people. It also loves rules, some of which are arbitrary at best but good luck telling anyone, ordinary folk just say, "well, science said so" and the ones who should know better don't have time for your nonsense, they have to submit 50 page grant applications to a review committee comprised of a cabal of cronies or they won't make full professor. /rant.

The rule for today is amygdala= fear. So no amygdala means no fear.

SM, who lacks amygdalas, was Fear Factored with snakes and spiders; they took her to a haunted house (though not a Japanese haunted house which doesn't so much scare you as destroy your soul forever); they made her watch clips from horror movies.

But she wasn't scared. She exhibited, and said she felt, no fear.

II.

Don't hit up a brain surgeon quite yet.

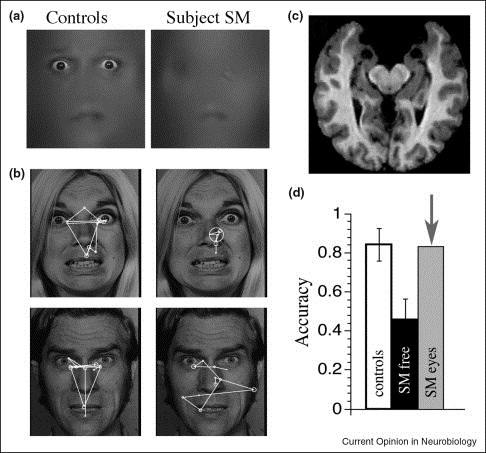

SM not only can't feel fear, but is impaired "in recognizing fear in facial expressions, and in aspects of social behavior thought to be mediated by emotions related to fear." Which seems consistent with the expected result of amygdalar damage.

But others noticed something interesting about patients with bilateral amygdalar damage, and by "patients" I mean the exact same patient as the one tested in the above article, "SM." They found that she was indeed terrible at detecting fear in faces-- but it was because she didn't look at the eyes. When she was told to look at the eyes, she had no trouble detecting fear.

("SM eyes" means SM was told to look at the eyes)

This is borne out by other studies which find that the amygdala is primarily involved in fear detection when you are looking at the person's eyes. Body positioning and gestures, fear displayed by the mouth-- the amygdala doesn't seem involved in processing fear from those cues.

So the incorrect interpretation is to say the amygdala is needed to perceive fear. A more correct interpretation is that the amygdala is involved in fixating and processing information about emotions coming from cues from specific contexts such as the faces' eyes. You can see why this interpretation doesn't make it to the internet.

II.

What's going wrong is that one way associations are made into two way relationships. It is true that the amygdala is routinely observed to be activated during conditioned fear responses, but that's not the same as saying that it is the amygdala that is necessary for experiencing fear.

On top of which the terms are ambiguous. What's fear? Another patient with the same disorder as SM had normal mood and affect, and I'll quickly point out that this man had no problem experiencing fear. But guess what happened at age 38: he developed panic attacks. Missing two amygdalas did not help him, but 75mg of Effexor did. Take that, anti-Pharma backlash.

Wired Magazine interviewed the Current Biology study's author:

"What that suggests to us is that perhaps the amygdala is acting at a very instinctual, unconscious level," says Feinstein.Well, not exactly. Another group had got hold of SM and this time flashed images of faces too fast to be detectable by the conscious mind. Normal people are able to detect fearful faces more easily than, say, happy faces. SM, lacking amygdalas, shouldn't show any difference-- but, in fact, fearful faces broke into her consciousness much more quickly than happy faces, and just as quickly as for normals. So unconscious perception is intact despite the absence of amygdalas.

III.

Though I've pointed out some inconsistencies in the studies of the amygdala-- not to mention the studies of SM-- the real "discovery" of these papers is this: all three of the "groups" I cited share at least one author.

Unless we are positing these authors themselves suffer from some kind of brain lesion, we need a better explanation for the discrepancies.

It isn't that they are not aware of their own findings, but that we are not aware of them. Unless you're motivated to look up everything any time you read anything, then each paper comes to you in a bubble. If you take it and read it and learn it, you will almost always get it completely wrong. It's worse if you're getting your science from the popular press, which is basically like reading only the 97th word in The Waste Land and then writing a synopsis. "It's about canasta, I think."

Most real neuroscientists-- not psychiatrists or even neurologists- understand that the common paradigm of structure-phenotype is overly simplistic.

More generally, the brain doesn't so much process information as apply a set of built in solutions to every single piece of information. It constantly learns and reorganizes, recognizes patterns and rebuilds.

In the case of the amygdala, it is involved in fear (conditioning), but it is more generally involved in making decisions based on incomplete information. It helps reduce ambiguity through learning. How the impairment of that facility manifests in an individual may be very different: SM feels no fear, the other guy gets panic attacks. Some people gamble more; or take more risks; or don't learn from experience. Etc. It's not just what's damaged; it's what each individual compensates with.

In other words, cutting out people's amygdalas is a terrible idea.

Feinstein says the new findings suggest that methods designed to safely and non-invasively turn off the amygdala might hold promise for those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Which PTSD sufferers? The ones who already have smaller amygdalas? Don't hold your breath, and anyway, we already have something that does this: Valium.

This isn't to say that a specific structure isn't important, but it is to say that the other structures are just as important.

IV.

Here's the kind of question that should be primary, not secondary, to the investigation of SM: what would you expect her to feel instead of fear? Think about this. If the amygdala does fear and she doesn't have amygdalas, what do you expect to happen when there's a spider on her face?

Probably, you'd answer nothing. You'd expect her just to sit there and stoic it as if it is all meaningless. "Spider. Hmm. Tickles."

But what she actually felt was wonder. And curiosity. And excitement.

I could find no one else with amygdalar damage who had this compensatory (?) response. She had the right amount of emotional energy, but she experienced it as excitement. The spider didn't turn into a duck, it turned into a parachute jump. Why?

---

You might also like:

Man In Coma For 23 Years Not In Coma

The Problem With Science Is Scientists

26 Comments