Grade Inflation

You're a professor and you grade the paper a C. The next day Type A Personality Only Child comes up on you, "how is this a C? I answered the question correctly, didn't I?" Yes, but you write like a nine year old, 80% of this is the syntactical equivalent of "umm" and "ahhh", and many of your sentences are minimally altered passages right from Wikipedia. "But this is a history class. Why are you grading my writing style?"

There's really no good way for a professor to respond to this nut. The depth of his stupidity precludes any explanation from being meaningful; he will not be able to understand that the writing is a reflection of the rigor of the ideas which is a reflection of the knowledge of the material and etc. So you give him an A and head to a strip bar. I sympathize.

Two explanations are commonly offered for grade inflation-- and let me clarify that the grade inflation people complain about is the kind that happens in the introductory survey courses. No one worries about grade inflation in the 400 level thermodynamics class. 1. Universities don't incentivize teaching, they incentivize research, so the teaching suffers. 2. Students are drunken idiots. While both have merit, let's see if there isn't another explanation that shrewdly protects the unconscious of most of the players..

II.

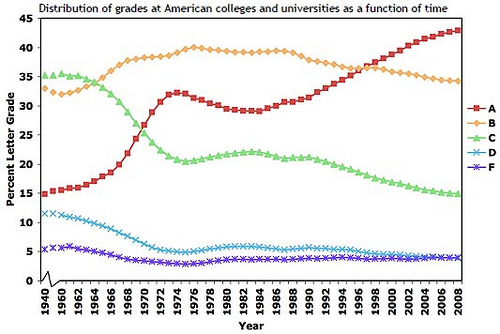

Here's a nice graph:

The

only surprising thing to me about this graph is nothing. Since no one over 90 is reading this, let's focus on 1986. What happened in 1986 that

changed the grading trend?

The

only surprising thing to me about this graph is nothing. Since no one over 90 is reading this, let's focus on 1986. What happened in 1986 that

changed the grading trend?Generation X went to college, that's what. Coincidentally, psychological researchers Twenge et al found that that was the year narcissism on campus began to rise:

And

by "coincidentally" I mean "not coincidentally." It's hard to tell a

growing population of narcissists that their schoolwork blows, so you

don't: A. Makes sense.

And

by "coincidentally" I mean "not coincidentally." It's hard to tell a

growing population of narcissists that their schoolwork blows, so you

don't: A. Makes sense.Most people stop their analysis right there, but you should really go the extra three steps and not just pee in the sink: now those students are 40. They grew up to be the Dumbest Generation of Narcissists In The History of the World, so narcissistic that not only are they dumb, but they do not know how dumb they are and cannot be told how dumb they are. They are aware that there are things they don't know, but they are certain that they have at least heard of everything that's worth knowing. Whenever the upper management guys at Chronicle Of Higher Education or The National Review pretend to disagree about the "classics" or "Great Books" or the "value of a liberal education," after five minutes it becomes clear that even they haven't read all those books, or most of them, or even a respectable minority, or three. They've read about them, ok, that's what America does, but when you finally pin them down and they admit they haven't read it-- which would be fine-- their final response is of the form "there's no point in reading Confessions now since we've all moved beyond that." Oh. And those are supposed to be the smart ones; everyone else in the generation thinks that the speed at which they can repeat the words they heard on TV or read on some magazine's website is evidence of their understanding.

II.

Which brings me to the main point, the other cause of grade inflation that no one ever talks about: in order for a grade to be inflated, a professor has to inflate it. In other words, grade inflation isn't the student's fault, it is the professor's fault. A kid can complain and whine/wine all he wants, but unless that professor buckles, there's no grade inflation. So the starting point has to be: why does a professor inflate a grade?

Yikes. Now that shudder you're feeling is not only why you never thought it, but how it is possible no one else ever brought it up? The answer is: every discussion about grade inflation has been dominated by educators.

The "college is a scam" train is one on which I'm all aboard, but that doesn't mean each individual professor has to be scamming students; there's no reason why he can't do a good job and teach his students something that they aren't going to get simply by reading the text. If a student can skip class and still ace the class, the kid is either very bright or the professor is utterly useless. Right? Either way, the kid's wasting his money.

And I know every generation thinks the one coming up after it is weaker and stupider, that's normal. But why would a professor who thinks college kids are dumb turn around and reward the King Of Beers with an A?

The answer is right in the chart and in a book by Allan Bloom that most college professors have read about. When that professor who was 40 in1986 was back in college in 1966, he was part of a culture that believed there are no "wrong answers, only wrong questions", like "you really think we should we stop shaving?" or "should we listen to something other than CCR?" And meanwhile the rate of As doubled. So now you have to put up your money: if you believe that grade inflation at that time masks/causes a real shallowness of intellect and education, then those students, now professors, simply aren't as smart as they think they are. Unless you also believe that bad 60s music and even worse pot somehow augmented their intellect.

And if you accept my thesis that narcissism prevents insight because it is urgently and vigorously self-protecting, then these same professors are not aware of their deficits. They think they know the material they are teaching simply because they are teaching it.

The problem is they are grading your papers and they do not know how to value a paper. Of course they can tell an A+ essay and they can tell an F- essay, but they are pretty foggy on everything in between. But they do not realize they are foggy. They think the problem is "the students complain." So they judge essays in comparison to others in the class or they fall back on the usual heuristics: page length, sentence complexity, and "looks like you put a lot of work into it."

And worse-- much worse, given that they are supposed to be educators-- they have no idea how to take a so-so student and make him better; what, specifically, they should get him to do, because they themselves were similarly mediocre students who got inflated As. Do you think they got their A in freshman analytic philosophy and said to themselves, "Jesus, I know I really didn't deserve this A, I better go back and try and relearn all this stuff." No: they went ahead and got jobs in academia, so that when a student comes to them asking, "how can I do better?" they can respond, "You need to apply yourself." Idiot. The system is broken. You broke it.

III.

Here's an example. Say your essay question is, "describe the causes of the American Civil War." Ok, so far everything the kid knows he learned from Prentice Hall, but something inside him thinks the answer is: LABOR COSTS. Hmmm. Insightful and unexpected, let's see what he does with it.

But there's not much he can do with it, there aren't many obvious resources to pursue this "feeling" he has. He does what he can. It's not that good. C. Grade inflation gives him a B.

Meanwhile, Balboa the el ed major searches carefully in his textbook and discovers the cause was... SLAVERY. He airlifts two sentences each out of five other books, asks for an extension because his grandmother died, adds nine hundred filler words including "for all intensive purposes" and "he could care less", and then waits in the parking lot to threaten you with "but this is a history class. Why are you grading my writing style?" He gets an A.

The problem is that the first kid is strongly disincentivized from pursuing his idea, from becoming a better thinker, in very specific ways.

First, and obviously, since the majority of the students are going to get an A, he just has to do just as well/horrifically as the average student, and if they're all writing about slavery with the enthusiasm of a photocopier then if he wants an A he better buckle down and learn the truly useful skill of masking the words of a Wikipedia page.

Second, he is very nervous about offering a professor anything that he didn't hear the professor explicitly mention, let alone endorse. What if it's "wrong?"

Third, because grading an essay is subjective, all professors try to make it objective by attributing value to measurable quantities which are actually stupid. For example: in most undergrad classes, the bibliography counts for 5%, maybe even 10%. How you (that's right, I said "how you") going to pad a bibliography with six sources when you can't even find one to support your thesis? So the pursuit of an interesting thesis is blocked by the 5% of the grade that comes from something that should count for exactly -20% of your grade, i.e. if you have a bibliography, you're a jerk.(1) This false value has two consequences: it "pads" the grade (e.g. the student already starts with an easy +5-30%) so it is easier for him to get an A. But more importantly, it is now easy for the professor to justify giving him an A. "His content wasn't that great, but the points added up; and besides: what the hell would I tell him to improve?"

I can't emphasize that last part enough-- the cause of the ridiculous grading is not the complaining of students but the convenience of the professor.

This is why if you are in a class and you feel the need to ask, "how many pages does this have to be?" and rather than look at you like you just just sneezed herpes on his face he instead has a ready answer, you are wasting your money. I get that you need the degree, I understand the system, but you're wasting your money nevertheless.

IV.

Take a quick scan of what these academics consider the highest level of academic scholarship: read their own journals. Here are the first three paragraphs of the first article ("Terrorism and The American Experience: A State Of The Field") in the temporally coincident month's Journal of American History, and I expect you to read none of them:

In 1970, just months before his death, the historian Richard Hofstadter called on U.S. historians to engage the subject of violence. For a generation, he wrote, the profession had ignored the issue, assuming that consensus rather than conflict had shaped the American past. By the late 1960s, with assassinations, riots, and violent crime at the forefront of national anxieties, that assumption was no longer tenable. Everywhere, Americans seemed to be thinking and talking about violence, except within the historical profession. Hofstadter urged historians to remedy their "inattention" and construct a history of violence that would speak to both the present and the past.1

Over the last four decades, the historical profession has responded to that challenge. Studies of racial conflict, territorial massacres, gendered violence, empire, crime and punishment, and war and memory make up some of the most esteemed books of the past generation. Yet on the subject of "terrorism," the form of violence that currently dominates American political discourse, historians have had comparatively little to say. Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, a handful of conferences have addressed historical aspects of terrorism, from its nineteenth-century origins to its impact on state building and national identity. Scholarly journals (including the Journal of American History) have devoted the occasional special issue to examining terrorism's roots and present-day implications. Within the historical profession, several book-length works have taken up episodes of terrorism, examining the production of both violence and state repression. Social scientists and journalists have offered sweeping global histories, tracing the problem of terrorism from antiquity to the present.2

As a result, we have a better understanding of terrorism's history than we did a decade ago, but it would be hard to classify this surge of work as a flourishing subfield or even a coherent historiography. Almost a decade out from 9/11, most U.S. historians remain hard-pressed to explain what terrorism is, how and when it began, or what its impact has been. There is little consensus about how best to approach the subject or even whether to address it at all. This is partly because the issue poses knotty political questions: How do we talk about terrorism without reinforcing the "war on terror" or lapsing into hopeless presentism? It also brings serious methodological problems: Is terrorism a word to be traced through centuries of semantic permutation? Is it an epithet to be applied to forms of violence we do not like? Is it a concept to be defined, however loosely, and followed through time?

Like any project that takes its cue from current affairs, constructing a historiography of terrorism requires caution and a light touch...

If a student wrote this I'd punch him in the bladder and get a good defense lawyer, assault charges be damned. I've deliberately avoided the easy targets like the po-mo journals; this is "the leading scholarly publication and the journal of record in the field of American history" and the author goes on like this for 20 pages. Can you trust this professor to grade an undergrad paper? The first two paragraphs are filler, meaningless noise in the guise of a sophisticated introduction. Maybe she can tell an A+ and she can tell an F-, I have no idea, but is she in any position to know a C from a B? And help you improve? Do you want to write like her? If you had questions about the history of terrorism, or terrorism, or history, would you call her?

I picked her because she was at random, but the same forces apply ubiquitously: academic journals are long, boring, poorly written academic-ese that no one reads because whatever insights or information they possess are buried in...the syntactical equivalent of "umms" and "ahhs." Even those who theoretically need journals to do their jobs every day (e.g. lawyers and doctors) avoid them.

Apart from boycotting any classes taught by these people I don't know what the solution is. Some professors cleverly include a "class participation" grade, and these professors pride themselves on using "the Socratic method." Sigh. Asking random students random questions is not the Socratic method, it's annoying, In order for it to be a true Socratic method, the professor would have to ask the student to state a thesis, get him to agree to a number of assumptions, and then masterfully show, through dialogue, how that agreement undermined his own thesis. In other words, the professor would have to have considerable fluency with his topic and be interested in each individual student, as an individual. Good luck with that. (2)

V.

If you reconsider grade inflation not as a function of the quality of the output but rather as the result of a hesitating lack of confidence about what constitutes good quality-- and again, I'm talking not about A+ and F- but the differences between the B and C levels where most "good" students are; and accept that, simply as a numerical reality, these "average" students are then the ones who (likely with the assistance of grade inflation) go on to become future academics, then a number of phenomena suddenly make a lot of sense. And the most important one is the one that students have long suspected but never dared say out loud: professors do not know the material they are teaching, but they think they do.

An American History professor may be considered somewhat of an expert because he's been teaching the Civil War for the past 15 years, but he's only been repeating what he knew 15 years ago for 15 years. And every year he forgets a little. How carefully is he keeping up with it-- especially if his "research interests" happen to lie elsewhere?

I know doctors who have been giving the same receptor pharmacology lectures to students for a decade. I know they are narcissists, not just because they are too apathetic to keep up with the field, but because it never occurred to them that receptor pharmacology might have advanced in ten years. They believe that what they knew ten years ago is enough. They are bigger than the science. These aren't just some lazy doctors in community practice, these are Ivy League physicians responsible for educating new doctors with new information. Yet the Power Point slides say 2001. "Well, I'm just teaching them the basics." How do you know those are still the basics? Who did you ask?

You think you philosophy professor re-reads Kant every year? The last time he did was in graduate school-- when his brain was made of graduate student and beer. Think about this. Hecko, has he even lately read about Kant? Do you think he tries, just to stay sharp, to take a current event and see what Kant might say about it? No, same notes on a yellow legal pad from Reagan II. Does he "know" Kant because he's been "teaching Kant" for 20 years? When in his life is he "challenged" by someone else who "knows" Kant? Seriously, think about this. For two decades the hardest questions he's been asked come from students, and he's been able to handle them like a Jedi. How could he not think of himself as an expert?

The sclerosis of imagination and intellect that inevitably happens over time will make it impossible for him to grade a paper that does not conform to his expectations. I don't mean it agrees with the professor, I mean his expectations of what a good paper looks like. Students already have a phrase for this: "What he likes to see in the paper is..."

So when it comes time to write a paper about Kant, it is infinitely less important that he understand Kant then it is for him to understand what the professor thinks is important about Kant-- and it is way easier to get through college this way. And if you have the misfortune of being taught Kant by a guy whose "research interests" are not Kant, forget it. You're getting an A, and he hates you.

VI.

This stuff matters, it has real consequences. When one narcissistic generation sets up the pieces for the next generation, and you put the rooks in the middle and leave out the bishops and hide one of the knights, and then you tell the kids that they lack the intelligence or concentration to really learn chess, you have to figure they're not going to want to pay for your Social Security. Just a thought.

Also: TAs are helping grade some of the papers, and some is worse than all. In order to ensure grading consistency, the essay answer has to be structured in a format that facilitates grading-- because if the professor can't value a B form a C, how can a TA? So the answer must mirror the six points in the textbook or the four things mentioned in class. This, again, means you shouldn't spend any time learning, you should spend it gaming the essay. So if the essay question is, "Discuss some of the causes of the Iraq War" you can be dead sure that "some" means specifically the ones the professor thinks are important. There may be others, but you're taking a big risk mentioning them. The TAs are just scanning for keywords. As long as they're in there, even in grammatically impossible constructions, you win. A. (3)

VII.

Here's one solution: abandon grades.

"But we have to have some way of objectively evaluating students!"

Haven't you been listening? You can't just suck the Red Pill like a Jolly Rancher, you have to swallow it. Grades aren't objectively measuring people, the whole thing is a farce. The grades are meaningless. Not only do they not measure anything, but the manner in which they are inflated precludes real learning. Stop it.

"Some grades aren't inflated." But how would anyone on the outside know? Can you tell them apart? The long term result will be: bad money drives out good money.

"Well, I earned my As." No you didn't, that's the point. I'm not saying you're not smart or didn't work hard, I'm saying you have no idea how good or bad you are, you only think you do.

"Just pass/fail? But how will employers know a good student from a bad student?" Again, you are avoiding the terrible, awful truth because it is too terrible and too awful: when employers look at a GPA, they don't know anything. The 3.5 they are looking at is information bias, it not only contains no information, it deludes you into thinking you possess information. You can't erase that 3.7 from your mind. In what classes, in what levels, against what curve? Just because employers do it doesn't mean it's useful. They use sexual harassment videos, too.

Grades do not only offer incorrect evaluations of a student's knowledge, they perpetuate the fiction that professors are able to evaluate. They can't. Again, they may be able to tell an A+ and an F-, but a B+ from a B? Really? That's the level of their precision? But a professor cannot ever admit that he doesn't have that precision, because it cannot enter his consciousness that he doesn't. "I've been teaching this class for 15 years." And I'm sure it gets easier every year.

VIII.

Speaking of Iraq: on the eve of the Iraq War many Americans got together to demonstrate. I'm not in the protest demographic, the only way I'm going to be at a march is if there's alcohol, but I accept the fact that a protest is sometimes the only way to be heard and the last resort against a government that has forsaken you. I get it. Ok. So I'm watching the protests on TV, and a lot of people quite obviously don't want to go to war, and want it stopped at all costs. And I see a group of people with signs walking behind a long banner, and the signs and the banner say, basically, "UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS AGAINST THE WAR."

I've no doubt that there wasn't a little bit of the old Vietnam nostalgia there, but what made me furious was the signs. They actually believed that identifying themselves as university professors was helping the cause? Did they think Americans were going to slap their foreheads, "wow, educated people are against the war, maybe I gots to rethinks this?" Yes, that is exactly what they thought.

They could not see that they were sabotaging their own cause, that anyone ambivalent about Iraq would either not think anything or be blinded by white rage, "look at these mother--" and vote for Bush six more times. These professors were coming from such a profoundly narcissistic stance that they didn't see this, or they didn't care. They may have wanted to stop the war, but what was much, much, much, much, much more important was to be identified as against the war, even if by doing that they were causing other people to support the war.

Here's what TV didn't show: the next day, those professors went to their classes, taught a bunch of anxious, restless but bored students stuff that they really had no business teaching, and later asked them to write essays that could be graded essentially as multiple choice questions so that they wouldn't really have to read them. If these professors didn't realize or care that that they were violating their own principles about war merely to self-identify, do you think they care about you? They have much bigger things to worry about. A.

---

1. Bibliography, as distinct from references. Anyone who produces a Bibliography without specific references as some sort of support of the truth of their idiocy is on notice. I'm talking to you, DSM.

2. An interesting educational experiment would be to come at things form a negative perspective. "Look, class, Hegel was a complete jerk, and his ideas were infantile pseudo-buddhism garbage. I'll give 50 points and a candy bar to anyone who can explain to me why." And see if that doesn't inspire the student to want to understand what Hegel was trying to say. I don't know if this will work. I know that a disengaged professor saying that Hegel is a great German philosopher and then reading lecture notes written back in 1986 on a yellow legal pad very clearly doesn't work.

3. Here's an essay I'd love to read, hell, love to write: "There are numerous "established" causes of the Iraq War, yet they almost always cite reasons that occurred after 1990. Please watch the 1975 film Three Days of The Condor. Other than a Tardis, what explanations could there be for director Sydney Pollack's ability to predict the future with such accuracy? Please discuss some of the events of the late 1960s to early 1970s that made the finale's prediction possible."

---

Also: Here is precisely one of these professors

102 Comments