September 19, 2011

The Contagion Is The Solution

wait... why can't I talk to anyone?

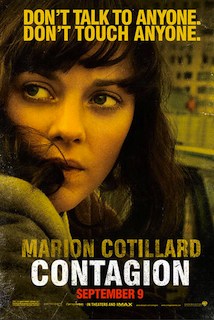

Seen Contagion yet? Here's a simple question: can you name one character?

Not the actor's name, the character's name. Take your time. Nothing?

A=A, and character driven movies, the kind Soderbergh is famous for, are supposed to be about characters.

Maybe this isn't a character driven movie. Maybe it's a documentary, aTraffic-style story about "what would people do if?"

But the movie doesn't depict them doing anything you wouldn't predict (die; panic; kill each other; attempt to profit; mourn; protect their own at all costs) or in a new way. So characters you're not emotionally involved in, doing nothing unusual... what's this all about?

I.

This is the opening scene:

Gwyneth is not driving, but is still holding a phone, unnaturally, with her left hand. Is she a leftie? No. Did she have a stroke? No. Look closely, she's married. Two ways to go with this: either this is a disaster movie about grief, or a disaster movie about about punishment. Well, she's calling from an airport and the guy on the phone isn't her husband. The hell you say?! That's right, she's having-- and this is a quote-- a "layover."

So maybe this is like a horror movie: sexual sin= horrible punishment; a subtext which is repeated later as her husband, Matt Damon, tries to protect his pretty-but-not-hot (=survives) teen daughter from her urges to be with her who-knows-if-he's-infected boyfriend. (The script which I did not find on The Pirate Bay maybe says her name is Jory, BTW, but the audience doesn't care.) Is it the virulently contagious virus Damon's worried about? Sure it is. That's why he pulls out a shotgun when he catches them after 15-900 minutes of close contact frolicking in the back yard. Jory looks flushed. He finally relents to the inevitability of penis and vagina at the end of the movie when boyfriend shows up at their house wearing the vaccination bracelet. Safe sex. Matt Damon smiles as they dance with each other, then walks away, I assume into oblivion. That's what single dads are good for, cuckolding and pass interference, and don't let the door hit you on the way out.

Back to the inception. Gwyneth is infected but she doesn't know it, and is shown partying in a Chinese casino, blowing on men's hands, and forgetting her sin phone at the bar, which a Ukranian model (=blonde harlot) returns to her, thereby ensuring all sexualized blondes are punished.

But not before their sins are visited on the son.

And being an American, you say, "wow, they killed a kid in a mainstream movie?" Quite gruesomely, I might add, but don't worry, you'll feel nothing. He wasn't really a kid, he was merely an extension of her (he was only Damon's step-kid, making Matt twice a cuckold), and he needs to die to free Matt Damon to return to his real daughter.

When a disaster strikes, the answer to "why?" is usually of the form, "endocytosis of the virus into the cell" or "plate tectonics and subduction zones" which is as satisfying as an imaginary bottle of rum. So we convert it to a narrative, a story, yes like a movie and yes like 9/11, to which the answer is always 100% the same: punishment for guilt. The only question is whose.

Gwyneth is Patient Zero, she is the cause of the outbreak, and if this was an ordinary movie about ordinary sin her backstory would be enough, it says, "this is a story about individual guilt." Oh, look: her lover was the very first person to die in Chicago.

But it's a "subtle" political piece like the kinds played on TV all day on 9/11/2011, in which the Towers fell not because terrorists flew planes into them but because of America's incessant meddling in the Middle East; the same meddling which, educated people all know, had nothing to do with the Arab Spring at all. So this is a story about collective guilt, about how we are all responsible.

If that's the story we're going to see, her sins have to be made general enough and collective enough to justify a global catastrophe. Hence, though she's blonde and an unrepentant adulteress, she's also an executive for a multinational mining company that destroys the rainforests. Now it makes sense why 2M people had to die.

Closing the narrative loop, the last scene is the big reveal, how it all happened: we see Gwyneth's company destroy a rainforest displacing a bat which infects a pig which gets cooked at the casino Gwyneth is in, infecting her. Justice is served, madame. Chef recommends.

II.

The ordinary way to read contagion/natural disaster movies is as an expression of collective guilt, what did we do to deserve this? Those who survive at the end are either those who don't really share in the collective guilt (e.g. natives, poor, women, minorities, and, in this movie's case, the CDC janitor's son) or those who "change."

That's the ordinary way. The reason this reading is wrong is that this movie wasn't made in 1376, but in 2011. Look out your window: those bipeds are narcissists. Narcissism wants no part of individual guilt, so it for sure as hell isn't going to take the fall for collective guilt. Collective guilt is created as a defense against individual guilt. The individual unconscious does not want any part of "we", especially if "we" did something and got caught. The unconscious only cares about "I".

Gwyneth Paltrow presents us with an interesting test of our psychology. Let's see how good you are at thinking in binary: when Judgment Day comes, will God judge her more harshly for being an adulteress or an executive in a mining company?

Oh, you're not religious? Then you are superstitious (-- "No I'm not at all, I'm just kind of OCD." Is that what the kids are calling it now?--) which means you don't deal in judgments but in root causes. Ok: why did 2M people have to die? Was it because she's an adulteress, or because she's a mining company executive? Pick one. You sure? Now why did her son have to die?

III.

Not knowing the characters makes it easy to focus on collective guilt, which is really someone else's guilt that you're benefiting by pretending to take on. Not knowing "Beth Emhoff" means you don't have to parse her individual guilt.

This movie could have been a straight "Beth is horny and she is punished" movie, i.e. an 80s slasher film. But this generation demands a defense against that kind of subversive thinking. So Beth's guilt is minimized in favor of featuring examples of collective guilt. Who caused 9/11? Nineteen two dimensional characters we don't know the names of. Ah, so 9/11 is payback for the sins of "The United States Of America" which means no one is looking to punish you specifically, because it's not your fault. It's "our" fault. Which means it's Bush's fault. Which means we're all off the hook now that he's gone.

But maybe taking responsibility for our collective sins is a noble, selfless act? No. The ego will do anything to protect itself, including publicly accept guilt for something that causes it to experience very little actual guilt. "We caused global warming!" Really? It was you? You drink yourself to sleep because you burn too many fossil fuels? You can't look a person in the eye because you drive an SUV?

IV.

Even before the virus kills a lot of people, people begin to panic. This is facilitated by the internet, played by Jude Law, who blogs about corporate greed, "the CDC is lying to you", and a holistic cure (forsythia) that Big Pharma of course doesn't want you to know about. (Also, it doesn't work.) But people start raiding pharmacies looking for it anyway. (1)

The virus, in theory, does not discriminate; but the movie makes it clear that information very much does discriminate. When Dr. Laurence Fishburne and his team at the CDC figure out that Chicago is next, he retreats to his office and secretly calls his girlfriend, "get out of Chicago, but tell no one."

But wait, there's a janitor standing behind him. "How much of that call did you hear?" asks Fishburne. "We've all got people," the janitor replies.

Which is further exemplified by what Fishburne's girlfriend does next: she talks to her people. "You have to promise to keep this a secret..." And then that people posts about it on facebook. We've all got people, and they all panic.(2)

but first, some shopping

but first, some shopping

Information is the parallel virus, but that is not a flippant comparison. Totalitarians of the world, take note: in the movie, information the public has is always bad for them. I do not mean the information is wrong. Jude Law's info about forsythia is wrong and thus troublesome; but the CDC's announcements about the virus are all accurate and stuff you'd insist you have the right/need to know. Yet that information is irrelevant. Having this information, are you cured faster? Are you better able to protect yourself than the obvious intuitive maneuvers?

The single reason to offer official information (and the movie distinguishes between "official"=valid=useless information disseminated via TV and unofficial=false=dangerous information traveling via internet) is that it sedates people; it is never to benefit them. Which is why it is more important to the perception of safety to keep the electricity going (which they do) than the food going (which they don't.) "We've identified the virus, it is called MEV-1." Oh, so that's what it is. Now we're getting somewhere.

All media is state run media, especially when it's not.

V.

A case study of individual vs. collective guilt.

Cobb's wife in Inception, Mal, in this movie plays a WHO researcher who travels to China to identify the source of the outbreak. Because of CCTV camera footage, she is able to observe Gwyenth infecting various other people, and the outbreak can be tracked.

Because Mal is beautiful, she is most likely be going to die. However, she's a) not American and b) a brunette with an atrocious haircut; which means she's not part of a) the collective guilt and b) probably not carrying any individual guilt. She could pull out of this.

Right after she and the Chinese researchers discover how the virus spread, she does something very, very important: she prepares to leave China. She's done with China, China is only important as a source of information and now of no consequence. There's no way those hominids could find the cure, and, anyway, there are dying people in the world she has to get to.

The Chinese researchers therefore kidnap her to a rural village and send a ransom note: if the WHO wants to see her alive again, they have send a crate of vaccines.

There are the two guilts: her individual guilt is her aloof cosmopolitanism, and her collective guilt is the WHO not caring about China. In order for this story to play out correctly, individual guilt must be minimized and collective guilt maximized. 1. Mal has to repent. 2. The WHO, as the collective guilt, has to take on her individual guilt, i.e. get more guilty.

1. The next time we see her, 45 minutes later-- she is in a makeshift, open air "classroom" teaching the Chinese children how to read. She is perfectly happy. I'll remind you that she has been kidnapped. In case the redemption isn't obvious enough, they club you with it: a lingering wide shot of the "classroom" reveals a huge cross on the roof. Note that Soderbergh's name is Soderbergh.

2. When the ransom is paid (crate of vaccines) and Mal is freed, she discovers that the WHO tricked the Chinese: the vaccines were placebos. Horrified, she runs back to the village, and the message is clear: no one cares about the little people, especially if they are Chinese. So a lot of people must die, but none of them Mal.

VI.

Another case study:

Dr. Fishburne gets his vaccine, but instead of giving it to himself he gives it to the janitor's son. In the language of narcissism, that act makes him a hero, and thus guarantees his survival. In the language of individual guilt, this is repenting for choosing "his people" over society.

Collective guilt takes on different meanings in different cultures. In America, collective guilt is always capitalist guilt.

Fishburne's act is a kind of message to global capitalists, "everyone has people they care about, your interests aren't more important than the working man's." Not explicit in the movie is the secret to many vaccines: herd immunity, i.e. unvaccinated Dr. Fishburne can benefit from other people's vaccinations. This is a metaphor for the popular refrain that global capitalists actually improve their own position when they help the poor because the poor will buy the goods that make them rich.

Now this is no longer an ethical question, "what is the moral thing to do?" but a cost/benefit one: "how can you maximize the benefit?" Which is exactly the way you'd want the question framed if you were a global capitalist. But in so doing one can avoid the nasty business of taking a moral stance, it frames everything in terms of consequences, comparisons of utilitarian benefit-- and consequently including individual guilt, which is the whole point of doing this. Was Gwyneth wrong to cheat? No, she's not a bad person, it's complicated. Is it wrong to loot? No, as long as you don't enjoy it.

It's interesting to see which position, moral or utilitarian, the movie chooses, because the movie is a reflection of it's audience's preference for one over the other. What do we want to be true in 2011?

The position the movie offers is this: Dr. Fishburne gives the boy the vaccination, but keeps the vaccination bracelet.

VII.

Implied in every disaster movie is "starting over," but starting over isn't the consequence, but the premise: "in order to start over and do it right this time, we need a catastrophe."

Now recall what is destroyed in a disaster: the unrepentant sinners and those who share in the collective guilt. What would starting over look like? It would be some recalibration of modernity. Where did modernity go wrong?

It went wrong with Patient Zero. Now our original Gwyenth problem is reversed: Gwyenth is not only an executive of an evil mining company, she's also a modern woman. Which means she can cheat when she wants and suffer no guilt. Yikes. As much as the image of a banana tree getting plowed by a bulldozer symbolizes a particular aspect of modernity, a blonde woman guiltlessly getting plowed by some other bulldozer is another aspect of modernity-- though not the cheating itself, but what she is able to think while she cheats. "She made mistakes, but she loved you very much," Matt Damon is told at the funeral home. That's true, and that's what makes it precisely so terrifying: Gwyneth had the physical freedom to cheat, and the emotional freedom to cheat and simultaneously still love her husband. A man understands a woman can be duplicitous, but the expectation is there's still an objective truth to her cheating: if she cheats, she likes him, not me. How can it be she likes him and me? How can she be two people simultaneously? What am I supposed to do with that when she comes home? That kind of existential freedom is to much to allow women to bear, and in any post-crisis world the first thing society does is take a few steps back into the safety of conventional roles. It happened after WWII and it will happen after the Great Recession, and everyone will think they made the individual choice to do it. After the Contagion has passed, Matt Damon's daughter's first order of business is to express her happiness and love through the last holdout of happily accepted gender roles: the high school prom.

VIII.

The preference of collective guilt over individual guilt suggests a comforting narcissistic arrogance: if this global catastrophe is, after all, our fault, then it is also under our control. We can stop it. That's why these disaster movies are very rarely about some catastrophe that isn't our fault: that would be too raw depiction of our existential dread. We need the defense of collective guilt to explain inexplicable events and offer a path to immortality on earth (if we act a certain way all will be well). This is especially important for narcissists who, not able to feel individual guilt, lack a redemptive path towards immortality after earth. The belief of control over the earth is all they have left.

It is the same narcissism that says, "we're destroying nature," which is a defense against being merely another part of nature. That it is a fact that we are destroying nature is secondary; the point is to believe it so that nature becomes a bit player in the movie of human exceptionalism. That it is a fact that nature is a bit player in the movie of human exceptionalism is secondary; the point is to believe it so that... and etc, until you individually have found meaning in the world.

You might think that individual guilt would be infinitely more amenable to modification than collective guilt-- if it's "your" fault, all you have to change is you. But try telling Gwyneth she shouldn't sleep with that guy, that it's wrong. "It's complicated," she'll tell you. Fixing "you", including the sins-- is nigh impossible, because those sins are you, the only way to stop doing them isn't to stop doing them but to change who you are. "You just don't understand the whole story" you'll explain in ten million sentences that say nothing. The part that I don't understand, of course, is how important it is to do do it to keep your identity intact. But I do understand. That's why I wrote this.

The trick to understanding disaster movies, and life, is to realize that the reason bad things happen is that we partly guilty and partly wronged, fully at the mercy of other people who use us and manipulate us; but that we still retain almost infinite power to alter reality and prevent bad things from happening. And the reason that that is the reason is that the alternative is there is no reason.

If 2M people die, you can be 100% certain that someone will find CCTV footage of a hateable adulteress destroying a rainforest, and that she'll get what's coming to you.

---

1. The media's preferred symbol for the disintegration of public order is looting, i.e the opposite of shopping. When Matt Damon goes into the looted supermarket, he's distinct from the other looters because he isn't enjoying it, suggesting he wasn't a big shopper, either. Consumerism was never in his nature, nor sexuality, as evidenced by two ex-wives, which is why he is the only person in the entire movie who is naturally immune to the virus. (Another note: in disaster movies, the ability to loot is what separates us from the animals. Once there's nothing left to loot, the people are then depicted as marauding cavemen, unless they are reorganized into a strict proto-capitalist economy. Welcome to Bartertown.)

2. Note that this must be in 2011: it didn't seem odd even to me that 51 year old medical doctor Fishburne has a girlfriend and no kids. In fact, the only character you see married in this movie is Gwyneth Paltrow, and you know how that works out.

Not the actor's name, the character's name. Take your time. Nothing?

A=A, and character driven movies, the kind Soderbergh is famous for, are supposed to be about characters.

Maybe this isn't a character driven movie. Maybe it's a documentary, aTraffic-style story about "what would people do if?"

But the movie doesn't depict them doing anything you wouldn't predict (die; panic; kill each other; attempt to profit; mourn; protect their own at all costs) or in a new way. So characters you're not emotionally involved in, doing nothing unusual... what's this all about?

I.

This is the opening scene:

Gwyneth is not driving, but is still holding a phone, unnaturally, with her left hand. Is she a leftie? No. Did she have a stroke? No. Look closely, she's married. Two ways to go with this: either this is a disaster movie about grief, or a disaster movie about about punishment. Well, she's calling from an airport and the guy on the phone isn't her husband. The hell you say?! That's right, she's having-- and this is a quote-- a "layover."

Soderbergh obeys the Rule Of Thirds

So maybe this is like a horror movie: sexual sin= horrible punishment; a subtext which is repeated later as her husband, Matt Damon, tries to protect his pretty-but-not-hot (=survives) teen daughter from her urges to be with her who-knows-if-he's-infected boyfriend. (The script which I did not find on The Pirate Bay maybe says her name is Jory, BTW, but the audience doesn't care.) Is it the virulently contagious virus Damon's worried about? Sure it is. That's why he pulls out a shotgun when he catches them after 15-900 minutes of close contact frolicking in the back yard. Jory looks flushed. He finally relents to the inevitability of penis and vagina at the end of the movie when boyfriend shows up at their house wearing the vaccination bracelet. Safe sex. Matt Damon smiles as they dance with each other, then walks away, I assume into oblivion. That's what single dads are good for, cuckolding and pass interference, and don't let the door hit you on the way out.

Back to the inception. Gwyneth is infected but she doesn't know it, and is shown partying in a Chinese casino, blowing on men's hands, and forgetting her sin phone at the bar, which a Ukranian model (=blonde harlot) returns to her, thereby ensuring all sexualized blondes are punished.

But not before their sins are visited on the son.

And being an American, you say, "wow, they killed a kid in a mainstream movie?" Quite gruesomely, I might add, but don't worry, you'll feel nothing. He wasn't really a kid, he was merely an extension of her (he was only Damon's step-kid, making Matt twice a cuckold), and he needs to die to free Matt Damon to return to his real daughter.

When a disaster strikes, the answer to "why?" is usually of the form, "endocytosis of the virus into the cell" or "plate tectonics and subduction zones" which is as satisfying as an imaginary bottle of rum. So we convert it to a narrative, a story, yes like a movie and yes like 9/11, to which the answer is always 100% the same: punishment for guilt. The only question is whose.

Gwyneth is Patient Zero, she is the cause of the outbreak, and if this was an ordinary movie about ordinary sin her backstory would be enough, it says, "this is a story about individual guilt." Oh, look: her lover was the very first person to die in Chicago.

But it's a "subtle" political piece like the kinds played on TV all day on 9/11/2011, in which the Towers fell not because terrorists flew planes into them but because of America's incessant meddling in the Middle East; the same meddling which, educated people all know, had nothing to do with the Arab Spring at all. So this is a story about collective guilt, about how we are all responsible.

If that's the story we're going to see, her sins have to be made general enough and collective enough to justify a global catastrophe. Hence, though she's blonde and an unrepentant adulteress, she's also an executive for a multinational mining company that destroys the rainforests. Now it makes sense why 2M people had to die.

Closing the narrative loop, the last scene is the big reveal, how it all happened: we see Gwyneth's company destroy a rainforest displacing a bat which infects a pig which gets cooked at the casino Gwyneth is in, infecting her. Justice is served, madame. Chef recommends.

II.

The ordinary way to read contagion/natural disaster movies is as an expression of collective guilt, what did we do to deserve this? Those who survive at the end are either those who don't really share in the collective guilt (e.g. natives, poor, women, minorities, and, in this movie's case, the CDC janitor's son) or those who "change."

That's the ordinary way. The reason this reading is wrong is that this movie wasn't made in 1376, but in 2011. Look out your window: those bipeds are narcissists. Narcissism wants no part of individual guilt, so it for sure as hell isn't going to take the fall for collective guilt. Collective guilt is created as a defense against individual guilt. The individual unconscious does not want any part of "we", especially if "we" did something and got caught. The unconscious only cares about "I".

Gwyneth Paltrow presents us with an interesting test of our psychology. Let's see how good you are at thinking in binary: when Judgment Day comes, will God judge her more harshly for being an adulteress or an executive in a mining company?

Oh, you're not religious? Then you are superstitious (-- "No I'm not at all, I'm just kind of OCD." Is that what the kids are calling it now?--) which means you don't deal in judgments but in root causes. Ok: why did 2M people have to die? Was it because she's an adulteress, or because she's a mining company executive? Pick one. You sure? Now why did her son have to die?

III.

Not knowing the characters makes it easy to focus on collective guilt, which is really someone else's guilt that you're benefiting by pretending to take on. Not knowing "Beth Emhoff" means you don't have to parse her individual guilt.

This movie could have been a straight "Beth is horny and she is punished" movie, i.e. an 80s slasher film. But this generation demands a defense against that kind of subversive thinking. So Beth's guilt is minimized in favor of featuring examples of collective guilt. Who caused 9/11? Nineteen two dimensional characters we don't know the names of. Ah, so 9/11 is payback for the sins of "The United States Of America" which means no one is looking to punish you specifically, because it's not your fault. It's "our" fault. Which means it's Bush's fault. Which means we're all off the hook now that he's gone.

But maybe taking responsibility for our collective sins is a noble, selfless act? No. The ego will do anything to protect itself, including publicly accept guilt for something that causes it to experience very little actual guilt. "We caused global warming!" Really? It was you? You drink yourself to sleep because you burn too many fossil fuels? You can't look a person in the eye because you drive an SUV?

IV.

Even before the virus kills a lot of people, people begin to panic. This is facilitated by the internet, played by Jude Law, who blogs about corporate greed, "the CDC is lying to you", and a holistic cure (forsythia) that Big Pharma of course doesn't want you to know about. (Also, it doesn't work.) But people start raiding pharmacies looking for it anyway. (1)

The virus, in theory, does not discriminate; but the movie makes it clear that information very much does discriminate. When Dr. Laurence Fishburne and his team at the CDC figure out that Chicago is next, he retreats to his office and secretly calls his girlfriend, "get out of Chicago, but tell no one."

But wait, there's a janitor standing behind him. "How much of that call did you hear?" asks Fishburne. "We've all got people," the janitor replies.

Which is further exemplified by what Fishburne's girlfriend does next: she talks to her people. "You have to promise to keep this a secret..." And then that people posts about it on facebook. We've all got people, and they all panic.(2)

but first, some shopping

but first, some shoppingInformation is the parallel virus, but that is not a flippant comparison. Totalitarians of the world, take note: in the movie, information the public has is always bad for them. I do not mean the information is wrong. Jude Law's info about forsythia is wrong and thus troublesome; but the CDC's announcements about the virus are all accurate and stuff you'd insist you have the right/need to know. Yet that information is irrelevant. Having this information, are you cured faster? Are you better able to protect yourself than the obvious intuitive maneuvers?

The single reason to offer official information (and the movie distinguishes between "official"=valid=useless information disseminated via TV and unofficial=false=dangerous information traveling via internet) is that it sedates people; it is never to benefit them. Which is why it is more important to the perception of safety to keep the electricity going (which they do) than the food going (which they don't.) "We've identified the virus, it is called MEV-1." Oh, so that's what it is. Now we're getting somewhere.

All media is state run media, especially when it's not.

V.

A case study of individual vs. collective guilt.

Cobb's wife in Inception, Mal, in this movie plays a WHO researcher who travels to China to identify the source of the outbreak. Because of CCTV camera footage, she is able to observe Gwyenth infecting various other people, and the outbreak can be tracked.

Because Mal is beautiful, she is most likely be going to die. However, she's a) not American and b) a brunette with an atrocious haircut; which means she's not part of a) the collective guilt and b) probably not carrying any individual guilt. She could pull out of this.

Right after she and the Chinese researchers discover how the virus spread, she does something very, very important: she prepares to leave China. She's done with China, China is only important as a source of information and now of no consequence. There's no way those hominids could find the cure, and, anyway, there are dying people in the world she has to get to.

The Chinese researchers therefore kidnap her to a rural village and send a ransom note: if the WHO wants to see her alive again, they have send a crate of vaccines.

There are the two guilts: her individual guilt is her aloof cosmopolitanism, and her collective guilt is the WHO not caring about China. In order for this story to play out correctly, individual guilt must be minimized and collective guilt maximized. 1. Mal has to repent. 2. The WHO, as the collective guilt, has to take on her individual guilt, i.e. get more guilty.

1. The next time we see her, 45 minutes later-- she is in a makeshift, open air "classroom" teaching the Chinese children how to read. She is perfectly happy. I'll remind you that she has been kidnapped. In case the redemption isn't obvious enough, they club you with it: a lingering wide shot of the "classroom" reveals a huge cross on the roof. Note that Soderbergh's name is Soderbergh.

2. When the ransom is paid (crate of vaccines) and Mal is freed, she discovers that the WHO tricked the Chinese: the vaccines were placebos. Horrified, she runs back to the village, and the message is clear: no one cares about the little people, especially if they are Chinese. So a lot of people must die, but none of them Mal.

VI.

Another case study:

Dr. Fishburne gets his vaccine, but instead of giving it to himself he gives it to the janitor's son. In the language of narcissism, that act makes him a hero, and thus guarantees his survival. In the language of individual guilt, this is repenting for choosing "his people" over society.

Collective guilt takes on different meanings in different cultures. In America, collective guilt is always capitalist guilt.

Fishburne's act is a kind of message to global capitalists, "everyone has people they care about, your interests aren't more important than the working man's." Not explicit in the movie is the secret to many vaccines: herd immunity, i.e. unvaccinated Dr. Fishburne can benefit from other people's vaccinations. This is a metaphor for the popular refrain that global capitalists actually improve their own position when they help the poor because the poor will buy the goods that make them rich.

Now this is no longer an ethical question, "what is the moral thing to do?" but a cost/benefit one: "how can you maximize the benefit?" Which is exactly the way you'd want the question framed if you were a global capitalist. But in so doing one can avoid the nasty business of taking a moral stance, it frames everything in terms of consequences, comparisons of utilitarian benefit-- and consequently including individual guilt, which is the whole point of doing this. Was Gwyneth wrong to cheat? No, she's not a bad person, it's complicated. Is it wrong to loot? No, as long as you don't enjoy it.

It's interesting to see which position, moral or utilitarian, the movie chooses, because the movie is a reflection of it's audience's preference for one over the other. What do we want to be true in 2011?

The position the movie offers is this: Dr. Fishburne gives the boy the vaccination, but keeps the vaccination bracelet.

VII.

Implied in every disaster movie is "starting over," but starting over isn't the consequence, but the premise: "in order to start over and do it right this time, we need a catastrophe."

Now recall what is destroyed in a disaster: the unrepentant sinners and those who share in the collective guilt. What would starting over look like? It would be some recalibration of modernity. Where did modernity go wrong?

It went wrong with Patient Zero. Now our original Gwyenth problem is reversed: Gwyenth is not only an executive of an evil mining company, she's also a modern woman. Which means she can cheat when she wants and suffer no guilt. Yikes. As much as the image of a banana tree getting plowed by a bulldozer symbolizes a particular aspect of modernity, a blonde woman guiltlessly getting plowed by some other bulldozer is another aspect of modernity-- though not the cheating itself, but what she is able to think while she cheats. "She made mistakes, but she loved you very much," Matt Damon is told at the funeral home. That's true, and that's what makes it precisely so terrifying: Gwyneth had the physical freedom to cheat, and the emotional freedom to cheat and simultaneously still love her husband. A man understands a woman can be duplicitous, but the expectation is there's still an objective truth to her cheating: if she cheats, she likes him, not me. How can it be she likes him and me? How can she be two people simultaneously? What am I supposed to do with that when she comes home? That kind of existential freedom is to much to allow women to bear, and in any post-crisis world the first thing society does is take a few steps back into the safety of conventional roles. It happened after WWII and it will happen after the Great Recession, and everyone will think they made the individual choice to do it. After the Contagion has passed, Matt Damon's daughter's first order of business is to express her happiness and love through the last holdout of happily accepted gender roles: the high school prom.

VIII.

The preference of collective guilt over individual guilt suggests a comforting narcissistic arrogance: if this global catastrophe is, after all, our fault, then it is also under our control. We can stop it. That's why these disaster movies are very rarely about some catastrophe that isn't our fault: that would be too raw depiction of our existential dread. We need the defense of collective guilt to explain inexplicable events and offer a path to immortality on earth (if we act a certain way all will be well). This is especially important for narcissists who, not able to feel individual guilt, lack a redemptive path towards immortality after earth. The belief of control over the earth is all they have left.

It is the same narcissism that says, "we're destroying nature," which is a defense against being merely another part of nature. That it is a fact that we are destroying nature is secondary; the point is to believe it so that nature becomes a bit player in the movie of human exceptionalism. That it is a fact that nature is a bit player in the movie of human exceptionalism is secondary; the point is to believe it so that... and etc, until you individually have found meaning in the world.

You might think that individual guilt would be infinitely more amenable to modification than collective guilt-- if it's "your" fault, all you have to change is you. But try telling Gwyneth she shouldn't sleep with that guy, that it's wrong. "It's complicated," she'll tell you. Fixing "you", including the sins-- is nigh impossible, because those sins are you, the only way to stop doing them isn't to stop doing them but to change who you are. "You just don't understand the whole story" you'll explain in ten million sentences that say nothing. The part that I don't understand, of course, is how important it is to do do it to keep your identity intact. But I do understand. That's why I wrote this.

The trick to understanding disaster movies, and life, is to realize that the reason bad things happen is that we partly guilty and partly wronged, fully at the mercy of other people who use us and manipulate us; but that we still retain almost infinite power to alter reality and prevent bad things from happening. And the reason that that is the reason is that the alternative is there is no reason.

If 2M people die, you can be 100% certain that someone will find CCTV footage of a hateable adulteress destroying a rainforest, and that she'll get what's coming to you.

---

1. The media's preferred symbol for the disintegration of public order is looting, i.e the opposite of shopping. When Matt Damon goes into the looted supermarket, he's distinct from the other looters because he isn't enjoying it, suggesting he wasn't a big shopper, either. Consumerism was never in his nature, nor sexuality, as evidenced by two ex-wives, which is why he is the only person in the entire movie who is naturally immune to the virus. (Another note: in disaster movies, the ability to loot is what separates us from the animals. Once there's nothing left to loot, the people are then depicted as marauding cavemen, unless they are reorganized into a strict proto-capitalist economy. Welcome to Bartertown.)

2. Note that this must be in 2011: it didn't seem odd even to me that 51 year old medical doctor Fishburne has a girlfriend and no kids. In fact, the only character you see married in this movie is Gwyneth Paltrow, and you know how that works out.

57 Comments