December 9, 2010

The Walking Dead: Not About Zombies

step 1

The Walking Dead is a show about zombies. It's a modern tale, with modern characters. They know about cell phones and Camaros, the CDC, and tanks. The show is also aware of its own artistic context, with numerous scenes referencing/honoring other movies.

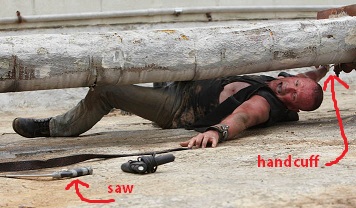

Mad Max knows there's not enough time to saw the handcuff

Mad Max knows there's not enough time to saw the handcuffThe "suspension of disbelief" necessary for this show is that zombies could exist. Once you accept that, everything else is America 2010. Given this, why do the characters never refer to the zombies as zombies? "Walkers," "geeks," "the walking dead."

Most modern zombie stories begin from the premise that the characters have "zombie" as part of their knowledge base (e.g. Zombieland.) But somehow these characters don't ever call them zombies.

One character, fed up with the inefficiency of his camp members' zombie hunting skills, says, "you're supposed to shoot them in the head. Everyone knows that." Agreed. How did you learn that? So how come you don't know what they're called?

II.

Let's play a game, a child's game, and if the outcome of this game is a little insight that keeps you from blowing your brains out or helps you crawl out from under the bottle then it will have been worth playing. The game doesn't have to be accurate to work. Interested? The rules of this game are words, and the name of the game is the rest of your life.

So turn over the First Zombie Question Card: what is it called when something obvious to everyone else never makes it to your consciousness? Repression. Repressed material comes back distorted, sometimes unrecognizably so.

Kind of like a zombie.

III.

Sigmund Freud is mostly remembered for his work on penis and vagina, but one of his biggest contributions to society was his observations about mourning, and cocaine. He went too far with the cocaine, and not far enough with the mourning.

Observation 1: no one can conceive, that is, perceive, their own death. Allow me to vamp: the ability to do so is an indicator of substantial pathology, especially a terminal one. There's no problem conceiving of everyone else's death, but any attempt to see your own fails because it requires you-- a first person singular perspective ("I am seeing what it is like.") An interesting experiment is to try to conceive it in second person, e.g. looking not at your wife mourning, but as your wife, through her eyes. Does that make your death seem more sad, or less? Time to rewrite the will.

Observation 2: All mourning is ambivalence. Ambi-valent, two conflicting powers: the cherishing and remembering and sadness part; and the guilt that perhaps maybe you wanted this person dead.

Wanted him dead? You're never too far from age 2, when your rage is magically powerful. At some point in your life, you thought it, and the unconscious never forgets even the briefest of hates. Sometimes the guilt over your hate has a convenient narrative: caring for a cancer-ridden, demented parent who exhausted your physical and emotional resources, and then finally(!) dies. That's going to generate a phew feelings, and they're going to cost you. All accounts must be settled at checkout.

IV.

It didn't always used to be this way.

Back in 1968, the first best zombie movie was made. How do you make a 60s zombie? You reanimate the dead. How they died doesn't matter, because the interesting part is that something had the power to reanimate them. Life after death?

Times change, and in our current time of narcissism all zombies appear through a new process: plague. That makes these zombies not so much the risen dead or the living dead as the incompletely dead. Life after life, life continuously-- even in zombie films we disavow death.

The zombie becomes the externalization of the ambivalence of mourning.

Paraphrasing from memory:

The narcissistic identification with the (loved) person becomes a substitute for love; the result is that even in the face of a conflict with the loved one, the love connection need not be abandoned. This substitute of identification instead of object-love is an important mechanism in narcissistic affections. This is a regression-- the first stage of object love is identification and is expressed ambivalently. The ego wants to incorporate this object into itself (oral stage). It wants to devour it.

Oh, I know, none of this makes sense until it happens to you. So turn over the second Zombie Card Question Card:

Apart from a scene showing a zombie eating a guy, what other scene is in all zombie movies?

A scene in which a main character confronts a loved one turned zombie. The rest of the previous zombie attacks are merely prelude to that one, specific, pivotal interaction. Quick, bolt the door, ambivalence is coming. Movies give the loved-one zombie a momentary flash of the old self-- is it remembering, is it a trap, or are you seeing what you want to see? This is the most important scene and how the living negotiate that bit of mourning determines if they'll be able to put the dead to rest, or are going to have be tied to them forever.

In The Walking Dead, there isn't just one such scene; the whole show is those scenes. Which brings us to Observation 3:

Observation 3: zombies are uncanny. Incomprehensible, yet incomprehensibly familiar...

V.

In Episode 1, a black man and his son are hiding out in their house, the only two humans surrounded by zombies. They save the main character, Rick Grimes, who also has a kid, but Rick is white. Is that just a coincidence? Of course (not). Black is in contrast to white, which would mean-- foreshadowing-- that the black guy is going to become quite dark.

But for now, why hasn't he and his son left town? Because wife got turned, and husband couldn't bring himself to re-kill her. And so zombie wife is still shuffling up and down the driveway, coming or going, staying or leaving? He's going to stay until he can finally put her to rest, there's some unfinished mourning to do.

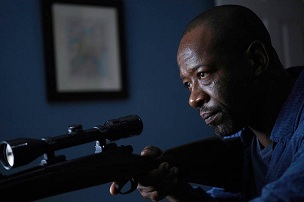

I miss you every single day. So this time I'm using a scope

I miss you every single day. So this time I'm using a scopeThe scope won't help. Incomplete mourning has affected his trigger finger, not his eyes, and so day in and day out he tries to (not) shoot her, repeating it over and over, working through it until he masters the material.

He can spend the rest of his life repetition compulsioning if he wants, but time marches forward and like everything else in life it comes down to a binary choice: he'll either get over her or get with her. It is inevitable.

That's why there's no sense in putting it off, and you certainly can't avoid it-- it follows you around.

That leaves the son, a small boy who isn't afforded the luxury of mourning. Children are much closer to the ambivalence of mourning, because when they (frequently) temporarily hate their parent they aren't confident of the physical limits of that hate, and if mom suddenly dies it's hard not to think you didn't have a wee bit to do with it. Which is why the job of proper mourning falls to the surviving parent-- lead by example-- and if he's smart he'll take advantage of the 6000 years of human history and allow the rituals of mourning to naturally lead the process, that's how the unconscious works through its conflicts. Learning by doing, until it becomes second nature. (The first nature died with the parent.)

And it's never too late, if you didn't do it right the first time and have been haunted ever since, you can always go back and perform the rituals more completely. "But I won't respond to those rituals because I'm not religious." It's not up to you; you're built for ritual. So are The Walking Dead characters, who completely against everyone's and their own survival instincts decide not to burn(/deny) the bodies of their zombie-murdered friends, but bury them all in time consuming (all of it), backbreaking graves. "It's a hundred degrees out here." If the digging's harder, the mourning is easier. And that's why they (living and dead) are able to move on.

Speaking of haunting, what's one potential consequence of a parent's incomplete mourning? The kid develops a strong belief that he can see ghosts and has ESP. If you're not ready to let go, then you'll hold on tighter; and if The Walking Dead scripts according to psychological flowchart, then little Walt will be revealed as psychic. Oh, wait, that's not Walt...

VII.

In a late-r episode, Sister B gets bitten and will soon become Sister Z, but Sister A can't bring herself to terminate the process. Instead, she sits with her sister as she lays dying, then undeading.

It's a very tense scene for us not because Sister B is going to die (how sad) but because we know she's going to be pissed when she does. But it's easy for us: we're not mourning. This is the interesting part: we're not mourning sister B, we're angry at sister A-- "shoot her, idiot!" And even when Sister Z reaches an undead hand towards the mourning sister's face, Sister A doesn't fight it. We are frustrated.

She finally does discharge our anxiety right into her temple, and phew. But hold on: for most of the season I thought they were twins, I couldn't tell them apart. Nor, given their character development, was it necessary to do so. Yet in one completely "unnecessary" scene, there's a long dialogue about how Sister A went off to college and was too busy for Sister B, and how guilty she felt that she wasn't there for her-- yes, they are that much spread in age. Hmm. That would make Sister A the mother figure. Now it gets interesting. Where's Dad?

Oh, there he is. So now this isn't about losing a sister but about losing a child. The ambivalence has taken on a different character. There's no fear in this mourning, just guilt, which makes this scene NOT "if you can't save them, join them" but rather "if you can't save them, your punishment is to join them." It's no coincidence that Sister-A can't shake the guilt and opts for punitive suicide in the season finale-- only to be lead, at the last minute, through the final steps of mourning by Dad. We don't really get a sense of his pain (it must be gigantic, that was his daughter, too) because the point is her pain, and a good Dad is beside the point. That's what Dads have to be: wolfram, stoic, pulling everyone's emotional weight when it's time to do so, because if not them, then who? That doesn't make their pain easier, unfortunately, but it's what's right. Does anyone remember right? Obviously not: that's why there are zombies.

VIII.

Let's go back to how uncanny zombies are.

[If] every affect belonging to an emotional impulse, whatever its kind, is transformed, if it is repressed, into anxiety, then among instances of frightening things there must be one class in which the frightening element can be shown to be something repressed which recurs. This class of frightening things would then constitute the uncanny

Mature people have a number of options for complicated bereavement. One option is to take on all that unconscious hostility and subsequent guilt ("I could have done more for him!") and develop a pathological, obsessive guilt. (The cure for which, if you're not much interested in auto-analysis, is to re-run the rituals, and run them right. It worked on Regan in The Exorcist, and she wasn't even Christian, let alone a Greek Catholic. And if that doesn't work, you run the rituals every so often, like memorials, keep retraining the unconscious. (And what about the person who doesn't want to do the rituals? When something is true for a trillion people over thousands of years, and you are firm in your belief that it is pointless, that's called resistance, and now the question changes to why you won't. The young are particularly susceptible to this, they don't want any part of your silly rituals and unskeptical beliefs because that would be to accept that they're no different than the trillion who have died before them. Don't worry ages 15-30, it's natural part of ego development. But keep in the back of your mind that no one is bigger than history, and certainly no one is bigger than death or it's consequences, and when the zombies come it wouldn't kill you to remember the rules.))

But immature people, i.e. cavemen, kids, and everyone in who is a main character in their own TV show (including The Walking Dead) have a less neurotic (so more psychotic-- the line between ego vs. id and ego vs. reality is the true bi-polar) option: projection. All my conflict shifted on to the dead himself. And there's enough anger there to keep them alive and make them come after me. Hence malevolent ghosts, vampires, werewolves (and oh, yes, "walkers," or whatever they are, they seem familiar but I just can't...) They are full of rage, not me. But a bullet to the head should solve that. Better them than me, after all.

Not for nothing, projection-- taking unacceptable emotions and attributing them as coming from the other person-- is what TV does so well, which is why we like it so much. Now you know why you love it when TV says George Bush is a selfish jerk and Lindsey Lohan is out of control slut.

IX.

What's familiar about the uncanny? The repressed material it represents. Are there examples?

Seeing your own double should be uncanny, and oh boy is it ever. So uncanny that they tell you if you ever meet your time traveled double, the universe will explodonate. How's that for a self-preserving narcissistic prohibition.

Try this: adopt an expressionless face and look in the mirror. Don't move, just look. That's you. Does it look like what you thought it would, exactly? Now imagine that it slowly smiles back at you. That's uncanny: it is the physical manifestation of repressed material.

"Huh? What repressed material?"

Is your smiling mirror-double good, or evil?

"Oh, that repressed material."

Your superego is moonlighting as a projectionist.

The double is an affront to your narcissism: "hey, wait a second, that's not really me, that's my Evil Double." No, it's you.

Now that we can see those repressed feelings manifested as a double, we also understand that we don't want to see that repressed material any more than we want to see a double smiling back at us in the mirror. The uncanny may be familiar, but it was supposed to stay hidden. If it doesn't stay hidden-- if it instead shuffles up and down the driveway-- you're going to freak out.

The uncanny doesn't defy explanation, it is obliterated by explanation. (Remember Lost?) In the first few episodes of the series, the zombies are uncanny. But the moment we see the scientist at the CDC watching zombie viral particles under a light microscope(!), the zombies are no longer uncanny. If they are the result of a virus then we don't have to wonder if they're the result of repressed feelings. Alternatively, if they are the result of repressed feelings, and those feelings are brought to awareness, then the zombie ceases to be uncanny (and exist.) Once you know the rules of mourning, zombies are an easy kill.

Let's go back to Sister A and Sister Z. Why don't we perceive Sister Z as uncanny, but the zombie wife in the driveway we do?

We don't see the sisters' interaction as uncanny, we're infuriated by it-- because we're a 3rd person perspective reality testing the zombie narratives, and we know the steps to properly mourn a zombie. The point of the scene isn't Sister Z, but Sister A-- so not uncanny. Just like listening to someone's supposedly uncanny dream. But if you consider Sister A's perspective, looking from her eyes, it must be very, very uncanny to see her sister as a zombie. Hence, the further we move away from the narcissistic position-- which allows us to recognize what's familiar-- the less uncanny it will be.

I've read that the supposed crucial advancement of the zombie folklore is the change to running zombies. I disagree; a more important change was the use of humor in zombie movies. Humor, especially irony, represents a shift in perspective, a new 3rd person awareness of your first person experience. This decreases the personal familiarity, the uncanny-ness, and hence is a defense against awareness of those repressed feelings. A funeral is no place for jokes, there's work to be done. Save those for the wake, not when they wake.

X.

It's popular to say the title, "The Walking Dead," really refers to the living people, not the zombies, and that the show is really about humans interacting with humans against the backdrop of a disaster. The zombies are thus "anything which causes society to regress to a more primitive state."

But those zombies aren't just anything-- they aren't an earthquake, they aren't bugs, they aren't aliens-- they are zombies, they are the uncanny, even if after hundreds of miles, deaths, and losses no one can identify them as such. Here we have a weakly TV serial about zombies and none of the characters know they are (the) zombies.

What do you get when ego and id aren't in conflict, in fact, they team up, against a common enemy-- reality? A reality which must often be denied in order to get some id-iPal satisfaction? You get America. What do you get when you get so good at denial, that you extend it to the inevitable? You get American zombies: denial of death.

The Walking Dead is a uniquely American show, about Americans. It depicts the unconscious processes involved in death and mourning with perfect articulation, because it is founded on denying what is obvious to everyone. "No," it says, "this is different."

---

You might also enjoy:

Unstoppable

Near Death Of A Salesman

When Was The Last Time You Got Your Ass Kicked?

----

http://twitter.com/thelastpsych

The Walking Dead is a uniquely American show, about Americans. It depicts the unconscious processes involved in death and mourning with perfect articulation, because it is founded on denying what is obvious to everyone. "No," it says, "this is different."

---

You might also enjoy:

Unstoppable

Near Death Of A Salesman

When Was The Last Time You Got Your Ass Kicked?

----

http://twitter.com/thelastpsych

125 Comments