Politics

Why Fly When You Have Tuberculosis?

Have you heard about the nut who, after being diagnosed with a rare tuberculosis, takes two transatlantic flights? Putting everyone at risk? Especially after doctors managed to track him down in Europe to tell him his tuberculosis strain was "extensively drug [isoniazid and rifampin] resistant" and very dangerous, and ordered him into isolation? Why would this nut do it?

The man told a newspaper he took the first flight from Atlanta to Europe for his wedding, then the second flight home because he feared he might die without treatment in the U.S.

He wasn't in the Sudan, or Kazakhstan-- he was in Italy. And he went to Prague to catch a plane to Canada SO THAT HE COULD DRIVE TO THE U.S.

I suggest everyone think long and hard about this, before we take any further steps down the road towards universal healthcare. You can't give away what you didn't pay for.

5/31/07 Addendum: AK (see comments) discovered that the guy is actually a personal injury lawyer. That's irony. And his new father-in-law is a CDC doc specializing in... go on, guess...

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

The Wrong Lessons Of Iraq

Don't ask me about Iraq.

But I do know something about our collective response to the Iraq war, to the Bush presidency, and to our times, and it says a lot about our cultural psychology. And it helps predict the future.

It's sometimes easier to evaluate one's personality, and thus make predictions about it, by examining the defense mechanisms the person uses. In difficult situations, specific people will use a small set of specific defenses over and over; so much so that we often describe people exclusively by that defense, e.g. "she's passive aggressive."

Taking Iraq and President Bush as starting points, and examining the defense mechanisms we use to cope with both, yields the unsurprising conclusion that we are a society of narcissists.

While this discovery is familiar to readers of my blog, what might be a surprise is what this heralds for our society politically and economically. It isn't socialism, or even communism, as I had feared. It's feudalism. It's not 2007. It's 1066.

Let's begin.

Continue reading:

"The Wrong Lessons Of Iraq" ››

Score: 55 (61 votes cast)

Score: 55 (61 votes cast)

Why We Are So Obsessed With Culpability vs. Mental Illness

As the thesis of this blog states: psychiatry is politics.

I'd like to offer an idea for consideration.

The reason there's so much give and take about whether Cho was ill or not, and whether he was culpable or not, has to do with what psychiatry actually is: the pressure valve of society.

Our society does not have a good mechanism for dealing with poverty, frustration, and anger. I'm not judging it, I'm not a left wing nut, I'm simply stating a fact; ours is not a custodial society, and it does little to "take care of" (different than help) these people.

So it has psychiatry, it fosters psychiatry, and it creates a psychiatric model in which these SOCIAL ills can be contained.

The inner city mom who smokes daily marijuana to unwind, with three kids who are disruptive, chaotic in school, etc-- society has really nothing to offer her. But it can't let her fester, because eventually there will be a full scale revolution. So it funnels her and her kids and everyone else like her into psychiatry.

Whether she "actually" has "mental illness" or not is besides the point. Without the infrastructure of psychiatry, hers would be an exclusively social problem with no solution. But with the infrastructure of society, her problem is no longer a social problem, and no longer the purview of the government (or fellow man, etc)--it is a medical problem.

Consider that one of the fastest ways for this woman to get welfare-- and ultimately social security-- is for her to go through psychiatry.

So, too, the angry, the violent, the frustrated...

Hence, discussions about whether mental illness reduces culpability are red herrings. It's about reducing culpability, it's about reducing society's obligation to deal with it.

Society is basically saying this (I'll quote myself):

...if they're poor or unintelligent, we will never be able to alter their chaotic environment, increase their insight or improve their judgment. However, such massive societal failure can not be confronted head on; we must leave them with the illusion that behavior is not entirely under volitional control; that their circumstances are independent of their will; that their inability to progress, and our inability to help them isn't their (or our) fault; that all men are not created equal. Because without the buffer psychiatry offers, they will demand communism.

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

This Is Not A Narcissistic Injury

I know it looks like one, but it's not. And why it's not makes every difference in predicting what will happen next.

My previous post described the modern narcissist, which is slightly different than the kind described by Kohut and others. In short, the narcissist is the main character in his own movie. Not necessarily the best, or strongest, but the main character. A narcissistic injury occurs when the narcissist is confronted with the reality that he is not the main character in his movie; the movie isn't his, and he's just one of 6 billion characters.

The worst thing that could happen to a narcissist is not that his wife cheats on him and leaves him for another man. He'll get angry, scream, stalk, etc, but this doesn't qualify as a narcissist injury because the narcissist still maintains a relationship with the woman. That it is a bad relationship is besides the point-- the point is that he and she are still linked: they are linked through arguing, restraining orders, and lawyers, but linked they are. He's still the main character in his movie; it was a romantic comedy but now it's a break-up film. But all that matters to the narcissist is that he is still the main character.

No, that's not the worst thing that can happen. The worst thing that could happen to a narcissist is that his wife cheats on him secretly and never tells him, and she doesn't act any differently towards him, so that he couldn't even tell. If she can do all that, that means she exists independently of him. He is not the main character in the movie. She has her own movie and he's not even in it. That's a narcissistic injury. That is the worst calamity that can befall the narcissist.

Any other kind of injury can produce different emotions; maybe sadness, or pain, or anger, or even apathy. But all narcissistic injuries lead to rage. The two aren't just linked; the two are the same. The reaction may look like sadness, but it isn't: it is rage, only rage.

With every narcissistic injury is a reflexive urge towards violence. I'll say it again in case the meaning was not clear: a reflexive urge towards violence. It could be homicide, or suicide, or fire, or breaking a table-- but it is immediate and inevitable. It may be mitigated, or controlled, but the impulse is there. The violence serves two necessary psychological functions: first, it's the natural byproduct of rage. Second, the violence perpetuates the link, the relationship, keeps him in the lead role. "That slut may have had a whole life outside me, but I will make her forever afraid of me." Or he kills himself-- not because he can't live without her, but because from now on she won't be able to live without thinking about him. See? Now it's a drama, but the movie goes on.

So if you cause a narcissist to have a narcissistic injury, get ready for a fight.

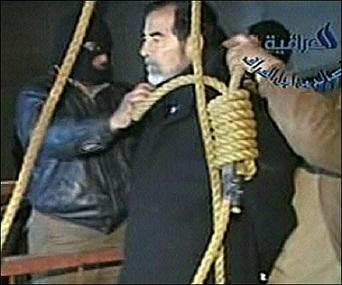

Saddam is not experiencing a narcissistic injury: he is still the main character in the movie. If he was sentenced to life in prison, to languish, forgotten, no longer relevant, no longer thought about, that would be a narcissistic injury-- then his rage would be intense, his urge towards violence massive. But who cares? There's nothing he could do.

But remaining the main character, he has accomplished the inevitable outcome of such a movie: he has become a martyr. Even in death, he is still the main character. That's why the narcissist doesn't fear death. He continues to live in the minds of others. That's narcissism.

I'm not saying executing Saddam wasn't the right thing to do, and I'm not sure I have much to add to theoretical discussions about judgment, and punishment, and the sentence of death. It doesn't matter what your political leanings are, what matters is we look at a situation that has occurred, and use whatever are our personal talents to try and predict the future.

I understand human nature, and I understand narcissism. And I understand vengeance. Saddam was a narcissist, but this wasn't a narcissistic injury.

This was a call to arms.

We should all probably get ready.

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Diana Chiafair 's Hot, but Is She Illegal?

from Pharmagossip, but also Dr. Peter Rost's site, edrugsearch (which actually has several rep-models), etc, etc. She's a rep from Miami (where else) who won Miss FHM 2006.

Meanwhile, Sunderland at the NIH plead guilty to "conflict of interest" charges-- he had received about $300k over 5 years from Pfizer while he was a director at NIH, but never disclosed the money.

All of medicine has rules about disclosing financial relationships. Any academic center, for example, requires you to list all financial entaglements that could be perceived as conflicts of interest, including grants, honoraria, stock holdings, etc. The idea, of course, is that money can exert undue influence, and at the very least the people around you should be aware of any potential conflicts of interest.

This includes conflicts of family members. If you are giving a Grand Rounds about how Zoloft is better than Lexapro, but your wife is a Zoloft rep, you could be benefiting financially by getting people to write more Zoloft which gets her bigger bonuses, so you have to disclose this relationship.

But if you are dating a Zoloft rep, you don't have to. There would be no way you could be profiting financially from her increased sales, and thus no need to disclose that relationship.

But there's the cryptosocialist hypocrisy. If it was really about protecting the public from conflicts of interest, we'd have to disclose dating reps as well. History is full of examples of people behaving unethically for the sole purpose of bedding a woman. Want examples? They all come from politics. Still want examples?

So why aren't we worried that I'm praising Zoloft because my rep is hot? Perhaps we should mandate all reps be ugly? You know, to protect society?

This sounds silly not because hot reps don't have influence, but because we're lying: it's not the influence that actually bothers us. It is specifically the money. "It's not fair that a doctor gets all that money from..."

So let's stop kidding ourselves, it's not about protecting the public after all; it's really about resentment that the doctor makes so much money off the people; that they get sent on trips first class while others can't afford healthcare; about the rich getting richer at the expense of the poor. &c., &c. Pick up any copy of the New York Review Of Books for further examples.

Taking the convenient moral high ground just because it has better soundbites ("the public has the right to know!") and saves us from having to perform any critical thought is lazy and unproductive. If you want to argue that doctors make too much money or Pharma's profits are excessive, we can go down that road and try for an honest and productive debate. But let's stop pretending these disclosure rules have anything to do with protecting the public from bias. They have everything to do with the current zeitgeist of income redistribution and class warfare.

---

As an cultural observation, look for the drug rep to become the next fetishized job, like cheerleader and nurse. A profession becomes sexualized not because the members are themselves hypersexual, but because they represent a particular balance of the "unattainable slut:" "sleeps with everyone but me." "e.g. the only reason that bitch (nurse or rep) isn't sleeping with me is that I'm not a doctor." In this way suppressed misogyny is given a cover story to make it acceptable. It's narcissism protected by an "if only" delusion. Violence is never far behind.

--- And there's your free association bringing me back to what I was really thinking when I saw Diana Chiafair's photo: marxism and healthcare reform. Hot rep--> fetishized--> commodity fetishism. Because we never see the labor that went into the objects, we never see that social relation; the laborer disappears, all that is left is the commodity to which we ascribe value-- fetishize it.

Continue reading:

"Diana Chiafair 's Hot, but Is She Illegal?" ››

Score: 7 (7 votes cast)

Score: 7 (7 votes cast)

If You Are Surprised By Vioxx's Risks, You're Fired

Continue reading:

"If You Are Surprised By Vioxx's Risks, You're Fired" ››

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Who Would Benefit?

Note the caption at the bottom. This is an interesting cover. No one would ever have thought to create a similar warning about the disastrous consequences of a poor fit for, say, Depakote. We know it has side effects, but using it would never be disastrous, right?

But why would bad therapy be disastrous? If psychiatry is so biologically based that the a bad environment is not the main cause of illness, why should bad therapy be so powerful? If bad parenting can't cause ADHD, how could bad therapy make it worse?

"The Art of Psychotherapy". Ok. But why the "science of pharmacology?" Because we sling "5HT2A" around like we know what we're talking about?

The sentence following that says, "Selecting patients for psychodynamic psychotherapy." Young, attractive, white females, perhaps? But they didn't mean that, of course. It's just a picture.

Almost no one appreciates-- and no one at all verbalizes-- how deeply the bias in psychiatry penetrates. It is no coincidence that psychiatry has been mixed up with SSI, welfare, criminal responsibility, etc. The "nature vs. nurture" debate is a red herring, a magician's distraction. It allows us never to have to say the following:

If they're rich and intelligent, and can understand how their behaviors impact their moods, we can help them to help themselves. And they won't want to take meds that cause side effects anyway.

But if they're poor or unintelligent, we will never be able to alter their chaotic environment, increase their insight or improve their judgment. However, such massive societal failure can not be confronted head on; we must leave them with the illusion that behavior is not entirely under volitional control; that their circumstances are independent of their activity; that all men are not created equal. Because without the buffer psychiatry offers, they will demand communism."

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Is Obstetrics Worse Than Psychiatry?

Turns out that Plan B emergency contraception does not reduce pregnancy rates. Big surprise. But the one difference was that those with easy access took it more often. (News article here.) So I stand behind my earlier question: why do oral contraceptives require a prescription, but this doesn't?

Coupled with the fact that 50% of abortions are done by women who have already had one abortion at least, and 18% are on their third or greater, and you have a social policy problem on your hands. While everyone is busy with political nonsense, we are missing an important segment of the population that is simply not taking responsibility for their behavior. Having three or more abortions in the United States has exactly nothing to do with abortion rights or women's health issues or access to contraception.

Oh, but it will be okay, won't it? OB/GYN will lead the charge? Sure. Context is everything: in the same issue of Obstetrics and Gynecology from which the above study came is an editorial by Douglas Laube, MD, President of ACOG. He suggests that OB/GYN has lost its way: med schools are not attentive to "differences in gender biology" (seriously.) And he suggests doing something about it:

I will create a task force to assess whether our specialty should adapt behavioral assessment techniques to evaluate candidates’ suitability as women’s health care providers.

I wonder if "suitability" will include social/political beliefs?

Well, he does quote Isaiah Berlin, who

"set in motion a vast and unparalleled revolution in humanity’s view of itself."

Unparalleled?

"His lectures helped to destroy the traditional notions of objective truth and validity of ethics..."

So, even if true (it's not,) is that supposed to be a good thing?

He's also upset that America doesn't pay its elementary school teachers enough.

Oh, and he closes his editorial with a quote "by the prophet Muhammed." Outstanding.

-------

Addendum: Let me explain what I mean by that last sentence, again, it's context: he's not a Muslim. He is (was) a Lt. Commander in the Naval Reserve. Are you telling me that in all of literature, the only quotation he could find to express his point is that one? Does he have a copy of the Hadith handy? What would you say if Mubarak (Pres. of Egypt) closed a speech with a quote from Augustine's Confessions? This is obviously a ploy, a pretense, he wants to show he transcends the childishness of politics and religion, he's about humanity.

That's where it all falls apart, that's where it stops being science and starts being dangerous.

I looked through six other articles/addresses by him; he seems to be a rigorous and thoughtful clinician and educator-- but-- and this is the but that is killing medicine and society-- he, like so many other doctors, wants to be a social policy analyst. No, no, for the love of God, no.

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

The Charade is Revealed-- We Are Doomed

Here's a question: can an antipsychotic be an antidepressant? Why, or why not?

The correct answer is that the question is invalid, because there is no such thing as an "antipsychotic" or an "antidepressant." We (should) define them based on what they do, not what they are. Therefore, Wellbutrin and Effexor are both antidepressants if and only if they both treat depression-- not because of some element of their pharmacologies, which are anyway different. Strattera, on the other hand-- which has a pharmacology (in some ways) similar to Effexor-- is not an antidepressant, only because it doesn't treat depression.

Following, just because something is called an antidepressant, or antihypertensive, it doesn't necessarily take on all the other properties or side effects of the others in its "class." Not all "antidepressants" have withdrawal syndromes (only SSRIs do). Not all antihypertensives cause urination (only diuretics do.) You wouldn't dare put a "class labeling" on "antihypertensives" of "diuresis."

So you see where I'm going with this-- except you don't.

I've previously yelled about the inanity of "antipsychotic induced diabetes" or "antidepressant induced mania" when they ignore pharmacologies, doses, and, of course, actual data.

But today I saw something that I now understand to be one of the signs of the Apocalypse. It is the new package insert of Seroquel, which just got a new indication for the treatment of bipolar depression. The new PI reads:

Suicidality in children and adolescents - antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (4% vs 2% for placebo) in short-term studies of 9 antidepressant drugs in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Patients started on therapy should be observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. SEROQUEL® is not approved for use in pediatric patients. (see Boxed Warning)

Stating the obvious: in none of these 9 studies was any patient actually ever on Seroquel; Seroquel itself is not associated with a risk of suicide; it's not even been tested for major depressive disorder; and, well, this isn't very rigorous science, is it?

Just because a is now called an antidepressant, it carries the same risk as the SSRIs? (Whether even SSRIs have this risk is besides the point.) Isn't that, well, racist?

This is not really about preventing suicide. If we were worried about suicide, really, then why 24 hours before the FDA posted this warning, no one cared about Seroquel's doubling of the suicide rate? Oh, because it doesn't actually double the suicide rate? Die.

So the game is clearly not about science, it's about politics, it's about liability, it's about money.

If this was honestly about about protecting children from suicide, we'd shrug our shoulders and say, "well, they're just very, very cautious, so we'll be careful and keep going." But that's not what this is. What this is factually inaccurate, misleading, and therefore more dangerous, more harmful. In a simple example, this warning protects no one for a risk of suicide-- no potentially suicidal patient is going to look at this and say, "well, crap, I'm not taking this." But it may prevent someone from taking it when they could actually benefit. See?

This is Structuralism gone very badly awry, Saussure just bought a pick axe and he's come looking for us all.

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Psychiatry Is Politics

Psychiatry is politics, it is politics in the way that running for office is politics. It is not a science, it is not even close to science, it is much closer to politics.

A doctor makes a diagnosis of a patient and writes it down on the chart. If it were science, then I should be able to evaluate the patient myself and come up with the same diagnosis. If it is a science but not an exact science, I should be able to come up with the same diagnosis most of the time, and the other times where I disagree I should be able to see why the other person thought what he thought.

But if I can guess the diagnosis without actually seeing the patient at all—but by knowing the doctor—then we do not have science, we have politics.

If you are watching the TV news with the sound turned down, and a Republican senator is talking, and the caption reads, “Tax Breaks for the Rich?” you can guess his position. In fact, the actual issue doesn’t matter—what matters is his party affiliation. Everything follows from there. Not always, certainly, but enough times that you don’t bother to turn the sound back up on the TV.

Psychiatry is the same way. It is very easy to determine who is considered a “great” psychiatrist, or a “thought leader in psychiatry” based on who is making the evaluation, and not on any merits of the psychiatrist himself. Down one hallway Freud is lauded; down the other he is villified; Kay Redfield Jameson is the hero. But their value, of course, is not at all dependent on what they did—it is dependent on who you are. Ronald Reagan was either a god or a devil depending on who you are, not who he was. It doesn’t seem to matter that most people can’t name one specific thing he did in office, what wars and battles he presided over, what he did or did not do to taxes. Ronald Reagan isn’t a person, he is a sign.

It’s even possible for me to guess the medications a patient is taking based solely on who prescribed them, and not on the symptoms of the patient. Importantly, the possible medications vary widely from doctor to doctor; it is wrong to think my predictive accuracy is based on any fundamental logic or science to medication selection that should be true across all psychiatrists. It's just his regular, unthinking, habit. "I like Risperdal." Are you an idiot? Are there internists saying, "I like insulin?"

Let me be clear: I’m not talking about doctors having unique insights into which medication might benefit a certain patient. (“I think Geodon could work really well here.”) I’m talking about each doctor having a set of drugs he prescribes with such regularity that I can guess them.

---

It stems from a lack of appreciation that mental illness is not a genetic disease, or even primarily a biological one, or even, surprisingly, a psychological one. It is a social disruption. On a desert island, no one can tell you are insane.

The key evidence against my position is that biology is so obviously relevant. There is a hereditary component to many mental illnesses; twins raised apart still often have higher concordance rates than non-twins. But this misses the point of the problem entirely. Consider diabetes: it is obviously a biological disease, with a heritable component. Much more biological than any mental disorder, because you can point to the dysfunctional biology in diabetes, but you can’t do that in bipolar disorder. But despite this biology, the environment is so massively important as to often overwhelm this biological component.

We can consider even further the actual relevance of genetics. Things that we assume are simple genetic outcomes are often more complicated than they seem. Eye color is every 7th grader’s primer for Mendelian genetics. But—surprise—there is no gene for eye color. There are in fact three genes for eye color, and the color is determined by the interplay of all three. So while you can guess eye color based on the parents, you are not always right—because each parent is giving three different genes.

It may be, in fact, true, that bipolar disorder is genetic. Perhaps overwhelmingly genetic, let’s say 40%. We go wrong because we consider genetics a “fixed variable”—we think we can only affect the other 60% of the factors. Right? Wrong; genetics is not fixed. Having a gene may be a fixed, but whether you express this gene or not is most certainly under outside control. Consider gender; absolutely genetic, correct? Not much one can do about it? But lizards can alter the sex of the progeny by changing the incubation temperature of the egg. Think about this. Now, is it not probable that the expression of the genes for bipolar have a lot to do with how you are raised? And we already know that environment affects gene expression, so I’m not speculating here.

Score: 10 (10 votes cast)

Score: 10 (10 votes cast)

There's A Shortage of Psychiatrists Somewhere, We Just Have To Find It

I was emailed a link to a 2003 article in the Psychiatric Times, which describes a maddening report out of California is so blatantly politicized that Arnold himself is embarrassed.

The report says, insanely, that there are not, and will not be in the future, enough psychiatrists to meet the needs of California. (Actual report PDF here.)

Well, not exactly true, is it?

When you say shortage, what do you mean-- 5000 psychiatrists for one state isn't enough? Oh, you mean that for some inexplicable reason, 63% of the entire state of California's psychiatrists work in the Bay Area or LA? Sounds like you have plenty of shrinks, they're just not distributed very evenly. Why would that be?

48% of all psychiatrists in California are in a solo or 2 physician practice. Hmm. 75% were male, 65% white. Hmm. Perhaps the problem is that your solo psychiatrists want to work in a nice area with good pay, and not in an inner city where-- ironically or tragically, your choice-- the need is greatest but the pay is least?

The nuts filing the report continue to lament that there aren't enough child and geriatric psychiatrists. Enough for what? Oh-- enough for Medicaid and Medicare. What did you expect? After suffering through a Child psych fellowship, why would go work for peanuts in a community mental health clinic, where you have a better chance of getting stabbed than getting rich?

Their complaints are misplaced and deluded. They do not reflect reality. Let me give you reality: the shortage exists in community (read: Medicaid) mental health, primarily because the pay sucks. But even there, the problem is not as dire as they make it sound.

First, even if there are numerically more psychiatrists seeing private patients, the community mental health psychiatrists see many, many more patients in a day. I'm going to guess the ratio is five to one. (Oh, you're upset they see them in ten minute intervals? When you give them a case load of 3000, what did you expect them to do? Psychoanalysis?)

Second, psychiatrists aren't the only ones providing "community mental health." Advance practice nurses (APN) and nurse practitioners (NP) also prescribe medications; in some states physician assistants can prescibe; and very soon psychologists will be able to prescribe, as they already can in New Mexico (and I think Louisiana.). (Care to retract your asinine prophecy, "the center predicts that there may actually be too many psychologists in the future.")

Third, primary care docs handle far more psychiatry than we can imagine. They just can't bill for it. (And so how good a job are they incentivized to do?)

The shortage is for "psychiatrists" proper (i.e. MD/DOs), not "providers of psychiatric medications."

The question then, uniquely, is whether we need psychiatrists proper at all to do community mental health. Are community mental health psychiatrists, as a group, better at diagnosing and treating than anyone else, for example an NP? Sadly, the answer is currently undeniably no. No one reads anymore, no one studies, and worse, the half-learned information that still lingers is so incomplete as to be misleading. Post residency, we get our info exclusively from drug reps and throwaway journals. Ergo, most residents are better psychiatrists than someone in practice ten years.

Woah-- be careful. Think long and hard before you hurl "clinical experience is more important" at me. Make sure you want to go down this road.

I am certain that I can take anyone with a college degree in any science, and in four months make them better than an above average psychiatrist. This is an open challenge to the APA. I'll repeat it: I'll take any person with a B.S. and in four months make them an academic psychiatrist.

But back to our "shortage" problem, or more accurately our distribution problem. The solution to this is elementary, but bitter. Either raise the standards necessary to be a practicing psychiatrist-- more audits and tests, greater documentation in notes, recertification exams with consequences to failing, and outcome/performance evaluations graded against other psychiatrists-- but also raise the pay, dramatically-- you can use the prescription drug savings when you implement my other plan-- so as not to lose the smart people to internal med or neurology; or lower the requirements so that more people can be prescribers, and lower the pay so that you can afford more of them. Either of these two will satisfy the growing "need." Which is better for the patient is up to California to figure out.

Score: 1 (5 votes cast)

Score: 1 (5 votes cast)

Vioxx

Merck's previous win in the Vioxx suit gets thrown out because the judge was concerned about the new criticism of the NEJM study.

What happened is an idiot's guide to forensic computing. Greg Curfman, executive editor of NEJM, was going to give a deposition in the trial of Frederick Humeston, an Idaho postal worker (or he was just curious about the data after Vioxx was pulled-- depends on which story you read) and so pulled the manuscript. Back in 2000 you'd submit a paper copy and a disk; NEJM says they worked off paper, so the first time they looked at the disk was Oct 5, 2004 (days after Vioxx was withdrawn.)

Here's the fishy part: on the disk was a table called "CV events," which was blank.

Time stamps in the software indicated that the table was deleted two days before the manuscript was submitted to The New England Journal on May 18, 2000. "When you hover the cursor over the editing changes, the identity of the editor pops up, and it just says 'Merck,'" Curfman says.

What's so terribly misleading about this and NEJM's "Expression of Concern" is this statement:

We determined from a computer diskette that some of these data were deleted from the VIGOR manuscript two days before it was initially submitted to the Journal on May 18, 2000.

This isn't true. First, the missing MIs were never in the table to begin with. Second, the table was deleted, but the data itself was still in the paper.

Now it is obvious the study attempts to minmize the thromboembolic risks. What do you expect from an academic study? Let me assure you-- if you think drug reps are biased, go find yourself a professor. So I acknowledge the criticism that the study is misleading. But.

But it's the social policy angle that gets me, the moralistic high ground of journal editors who are far worse than study authors. The gateway to hell is peer reviewed.

The article says Curfman was deposed by plaintiff's lawyers. Was Curfman paid by them? It doesn't mean he's biased, but if you have to disclose Pharma sponsorship, don't you think you should disclose lawyer sponsorship? (and I am looking to find out if he was indeed paid.)

As I have absolutely no interest whatsoever in the actual outcome of these trials-- my interest is really about how doctors butcher science and promote themselves to senators-- but, we should take a look at what this revelatory missing data says.

What they found was that with the inclusion of the missing data, the rate of heart attacks would have been 5 times greater than naproxen, not 4 times. 0.5% vs. 0.1%.

Just to put this in perspective, of course, you should know that the missing data was three more heart attacks, raising the number of patients with MI from 17 to 20 (out of 4000+ patients), vs. 4 in tha naproxen group.

BTW, "five times" and "four times" may sound like big differences, but they do not even approach statistical significance in this study.

BTW, strokes were the same in both groups. Not that anyone cares, of course.

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Plan B Emergency Contraception: Doctors Out of Their League, Again

"In a long overdue concession to science, the Food and Drug Administration could finally, grudgingly, be ready to allow an emergency contraceptive to be sold without a doctor's prescription." (USA Today Opinion 8/2/06)

"Concession to science?" Wow!

I have admittedly almost zero interest in the way Plan B has become a proxy war for anti/pro abortion armies. But when doctors become social policy analysts I take note.

Why are "scientists" saying that this drug should be sold without prescription? Why should oral contraceptives require prescription, but this should not? Or, to reverse it, if this doesn't need a prescription, then what does? How do we decide what needs a script and what doesn't? Expediency? Political advantage?

The argument that this is an important option in the event of a pregnancy scare is premised on the notion that Plan B will be rarely used. This is false. It overlooks a very key point: every unprotected sexual intercourse is a pregnancy scare. And people usually have a lot of sex.

Look at it this way:

Before Plan B: you're a woman, you have sex. You're worried-- not really worried, it's not the "right time of the month," he pulled out, etc, etc, but it's in the back of your mind. But there's nothing you can do, too late now, so you just wait it out.

After Plan B: you're a woman, you have sex, etc, etc, but now exists a safe, non-prescription way to ensure you don't get pregnant. Why wouldn't you take it, just in case? Even if the chances you are pregnant are really small-- Why not? What does it hurt? It's safe, the FDA said so, and even put it over the counter. A little nasuea to guarantee you don't get pregnant?

See? It's a no-brainer.

But what about the next night? And the next? What if you have sex-- 10 times a month? It's not frequent enough to embark on the oral contraceptive-- after all, you don't have that much sex, you can't afford to go to the doctor, you don't have the time, etc-- but you know, Plan B is available in seconds... Why not?

I know men who take Viagra "just in case." (And that requires a prescription.) You think this will be different?

Look, Plan B might actually be safe, even if taken every day. But isn't every-day-Plan B chemically identical to an oral contraceptive-- which requires a prescription? And if it isn't safe taken daily, why wouldn't a prescription be required? I should point out that Plan B actually has three times more hormone in it than an oral contraceptive. Hmm. Is taking three birth control pills a day safe? Anyone?

Again, this isn't about whether Plan B is moral or a social necessity-- something on which doctors are no better equipped than lumberjacks to pass judgment. This is about whether Plan B should need a prescription, based on the drug's safety.

This isn't about women's rights or abortion or anything else. It's about "scientists" picking and choosing what they want to believe; about becoming intoxicated with the power to drive social policy, and manipulating the infrastructure of the discipline to generate a smokescreen of science to support them.

Remember: these are the same people who discovered (read: decided) Vioxx causes heart attacks and Zoloft drives people insane-- years after their release-- but Plan B is so safe it doesn't need a prescription.

If I were a class action lawyer, I'd start clearing my desk...

------------------

Levonorgestrel: WHO recommends 1.5mg as a single dose; "Plan B" is .75mg in two doses (12hrs apart.)

Assume the average OCP has 0.25mg of levonorgestrol. (a levonorgestrol-only OCP, called Microval, has only .03mg).

Addendum 11/24/06: Turns out that Plan B emergency contraception does not reduce pregnancy rates. Big surprise. But the one difference was that those with easy access took it more often. (News article here.) My post about this here.

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Missing The Point At The NY Times

This time by one of our own (academic psychologist, Harvard) in an Op-Ed, entitled, "I'm Ok, You're Biased."

The premise is summarized here:

Doctors scoff at the notion that gifts from a pharmaceutical company could motivate them to prescribe that company's drugs, and Supreme Court justices are confident that their legal opinions are not influenced by their financial stake in a defendant's business, or by their child's employment at a petitioner's firm. Vice President Dick Cheney is famously contemptuous of those who suggest that his former company received special consideration for government contracts.

Which would be an ok, if not tired, set up, except for the very next sentence:

Voters, citizens, patients and taxpayers can barely keep a straight face.

It's the populism of the message that is laughable. So doctors, lawyers, Supreme Court Justices and others have no idea that they're biased, but the average joe does? Seems pretty unlikely. But-- maybe they are biased and it's okay.

And the proposed solution, of course, is the same knee jerk ineffectual nonsense proposed before:

In short, doctors, judges, consultants and vice presidents strive for truth more often than we realize, and miss that mark more often than they realize. Because the brain cannot see itself fooling itself, the only reliable method for avoiding bias is to avoid the situations that produce it.

There's that determinism so popular among those who feel powerless.

I hope that the irony of the NY Times, through a psychologist, preaching about objectivity is not lost on anyone. It is so bad at that paper that both the right and the left simultaneously blast it for overt bias. No wonder that the NY Times stock has lost 50% of its value in two years.

Why not discuss the bias of journalists? Or, more importantly, why are they assumed immune from it? This isn't an idle political question, it is the very essence of this debate.

I'll state it explicitly: first, the reason it doesn't matter if doctors are biased (and why it matters very much if journalists are) is because medicine is supposed to be a science. If it is a science-- receptors and all-- then it shouldn't matter what I think, it should matter what is true. I can delude myself and say that seizure drugs are mood stabilizers for the long term; but that doesn't make it true. But if you want to actually see if it is true, you have to look it up. And don't come back with "one negative study doesn't disprove its efficacy." This is science again: it's not up to me to disprove its efficacy, it's up to you to prove it has any.

So the real question isn't bias, it's whether medicine in general is paying attention to its own data. Do we read our own studies, or hope the "thought leaders" will, and then write us a synopsis? Do we believe it because Harvard said so? Is this science, or a cult of personality?

Second, when discussing medicine, the question of bias is not the important one. Yyou have to ask what the harm is. Thie bias isn't harmful to science because science should be able to stand on its own. The bias is only harmful to patients-- so the real question we should be asking is not if there is bias, but if it harms patients. Ready: pretend a family doc gets paid $800,000 by Pfizer to prescribe only Lipitor, no Zocor, Mevacor, etc. What, exactly, is the harm? It's not snake oil: in all the anti-pharma controversy, no one is accusing them of selling a product that doesn't do what they say it does. So unless you can tell me which patient shouldn't get Lipitor, but should get Zocor, then you can't argue this hurts the patient. I'm not saying it isn't sneaky, or unethical. But unless you can show the harm, you can't say it's harmful. That's what's relevant.

But we're not really worried about patients, are we? That's a screen. What this is all about is our own impotence; anger against people who are perceived to have power. We don't even actually believe our own nonsense. This is the same argument against Vice President Cheney. If everyone is so sure that the Iraq war was about oil and Halliburton, why didn't everyone buy Exxon and Halliburton stock back in 2002? It's fun to criticise, I know. But belief without follow through is pointless. If you're not willing to act on your own beliefs, why should anyone else even listen to your crazy beliefs?

I'm not saying doctors and politicians aren't biased. I'm saying we should worry about the things that actually matter. Want to start somewhere, Daniel Gilbert? Academic medicine, and the journals that are their propaganda arms. These people aren't scientists, they are science journalists. And they are very much biased. Don't believe me? Call me when you look up everyone's supporting references.

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

CATIE: And Another Thing

Score: 3 (3 votes cast)

Score: 3 (3 votes cast)

The Other Abortion Question

For those who live and breathe the abortion debate, it may be worthwhile to personalize the issue and see if anything changes. Certainly, Rick Santorum has done this.

If you do not already know the story, Senator Santorum told it himself on Fresh Air in September 2004. Briefly, at approximately 20 weeks gestation, he and his wife learned the fetus had a terrible disorder that would likely result in the fetus’ demise. They had three choices: carry the fetus to term, when it would inevitably die; abort the fetus; or try a risky surgery on the fetus (which was still inside the womb) which had a low probability of success. The Santorums, true to their faith and their principles, reasoned thusly: if this was a five year old child, there would be no debate. They went with the surgery.

As tragedies go, this was a big one, as the surgery failed, the fetus died, and the mother suffered complications. However, the story clearly indicates how one should reason if one believes life begins at conception. This is the point for the Senator; it is illogical to argue any differently. If we are debating the abortion issue, this is a hard argument to rebut.

But I am not, here on this blog, interested in the abortion issue specifically; I am interested in another question. It is this:

Who pays for this surgery?

It is not an academic question. Senator Santorum has the benefit of almost infinite medical resources. If we are going to force Medicaid patients to make a similar choice, we have to ask this practical question.

Many are not going to like having, depending on your perspective, a moral or privacy question reduced to money; but that is precisely the problem. Accountability. In the end, someone has to pay.

Only the schizoid will argue that abortion should not be an option even when the mother’s life is in mortal danger; and only the amorally unrealistic will fail to realize that there is something psychologically wrong with a woman who has had three, four, five abortions. (This is not so unusual: it is 18% of all abortions.) You may think it is your right to have as many abortions as you need, and you may be right; but there is still something wrong with you.

Not permitting abortions requires an explanation of how we're going to pay for surgeries like the Santorums's. And if you want to keep abortions legal, you have to tell me how we're going to pay for them; or for any complications that result from them.

Either healthcare is a right, like due process; or it isn’t, like driving. Either one you pick, you must be accountable for the consequences of your selection, for example, its effect on the abortion question; similarly, your stance on abortion must include an discussion of cost. Even if this is,a fter all, a moral question, someone still has to pay for it. I recognize this tarnishes the purity of the academic dialogue. It’s not pretty, it’s not clean, but it’s reality. And if you think that money is not a relevant factor here, then it almost certainly means you are not going to be the one who will have to pay.

This applies to other questions beyond abortion, of course. If someone discovers a cure for AIDS, but it costs ten million dollars, does everyone get to have it?

When the universal healthcare nuts draft a plan that includes how they are going to pay for the unintended consequences of an insufficiently reasoned abortion provision (or restriction), give me a call. Until then, wovon man nicht sprechen kann....

Score: 8 (8 votes cast)

Score: 8 (8 votes cast)

Pedophilia Makes You Stupid

Homeland Security Official Charged in Online Seduction

The system has failed.

Plot synopsis: DHS press secretary is caught in online sting, as he has sexual online chats to what he thinks is a 14yo girl but is really a cop.

Seriously, what's wrong with these people? Do you need a 14yo so badly, at any cost, you're willing to tell them you actually work for Homeland? Is that supposed to turn on 14 year old girls?

You would think the deputy press secretary of Homeland Security would know that he could be easily caught on the internet trying to solicit sex from a minor, or at least that the Department would know what he is doing on their computers. But he doesn't, for two reasons: a) he's stupid; b) in fact, the Department doesn't know what he is doing, because the Department is stupid.

I'll do you one better: no one traffics kiddie porn on IRC if they have half a brain in their head. You want to traffic kiddie porn? Make your connections over online games like WoW, Everquest, or Halo. In the case of the former two, the chat conversation works as well as irc, and in the case of the latter, it's voice traffic. In no case is the transcript or anything else logged. I bet there's more weird crap happening in online games than you'd want to know.

Add to that freenet, which is basicaly encrypted decentralized bittorrent with invite-only peers, and you've got a pretty robust digital underground.

Score: 7 (7 votes cast)

Score: 7 (7 votes cast)

Nature Weighs in On What Is True

and turn out to be wrong.

There's been something of a controversy raging over the best place to get accurate information.

Specifically, there's a free, user-written encyclopedia called wikipedia at http://www.wikipedia.org that competes with the

Encyclopedia Britannica. The idea is that anyone who uses wikipedia can edit any story. So if you happen to be reading an article that has an error in it (for example, if it says the Constitution was ratified in 1798) you can correct it with a few clicks (e.g. you change it to 1789). Aside from controversial topics (where articles are edited constantly to favor one

opinion or the other), the "hard facts" articles on science, culture or history are fairly decent. Or so they seem at first glance.

The controversy is this: Britannica's editor in chief went on record (in a newspaper article I can't find) stating that Britannica is a better, more reliable source of "knowledge" because it's a closed controlled editing environment, where articles are researched, edited, and reviewed internally by academics who are experts in their respective fields.

Wikipedia responded saying it doesn't need all that editorial oversight because any error in an article is corrected relatively quickly by an expert in the field.

The essence of the argument is "top-down" (Britannica) vs. grass-roots/bottom-up (wikipedia), or, to put it more succintly, does the existence of a gatekeeper for knowledge improve the quality, accuracy, and veracity of knowledge?

The debate matters for two reasons: (1) at some point people have to agree on the basic facts of whatever they are talking about, and (2) there needs to be a place where you can find the core true facts about any subject.

So anyway, the medical journal Nature decided to compare the two sources of knowledge:

http://www.nature.com/news/2005/051212/full/438900a.html

Now you may ask what the hell business is it of Nature's (a quasi-medical journal) to do this (review the accuracy of encyclopedias), but that's my point and I'll get to that in a second.

Anyway, surprise surprise, Nature says that in the case of science articles, wikipedia is better. This was not unexpected - wikipedia claimed all along that it amounted to enabling peer-review of its articles by readers, and Nature, of course, is all about peer-review.

Britannica responded, finding errors in Nature's methodology (warning: pdf ahead, but it's worth reading if you think for a second Nature should be trusted to do anything):

http://corporate.britannica.com/britannica_nature_response.pdf

concluding that the study was bogus, and that Britannica had far fewer errors and omissions than Nature claimed.

What interests me here is not the accuracy of Wikipedia vs. Britannica, but why Nature feels it is in any position to examine this.

Here is Nature's response to Britannica's criticisms:

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7084/full/440582b.html

Here's the line to focus on:

"Britannica complains that we did not check the errors that our reviewers identified...but there is a more important point to make. Our reviewers may have made some mistakes — we have been open about our methodology and never claimed otherwise — but the entries they reviewed were blinded: they did not know which entry came from Wikipedia and which from Britannica."

For the record, Nature says this is how the test was

conducted:

"Each pair of entries was sent to a relevant expert

for peer review. The reviewers, who were not told

which article came from which encyclopaedia, were

asked to look for three types of inaccuracy: factual

errors, critical omissions and misleading statements. 42 useable reviews were returned."

And this, my scientician friends, is why medicine isn't a science. Nature is saying that its methodology is sound because the entries they reviewed were blinded - BUT WHO ARE THE PEER REVIEWING EXPERTS, WHO SELECTED THE ENTRIES, AND ACCORDING TO WHAT CRITERIA?

You cannot excerpt an article describing something and then test the excerpt for omissions. Furthermore, the excerpting is not blinded, and the person excerpting things may have a different opinion of what can be safely left out than the person doing the review.

Nature's mistake is assuming that the expert is always right. If the expert disagrees with Britannica, then Britannica is wrong. You should be able to test the accuracy of an entire encyclopedia article *by giving it to multiple experts*. Not the other way around, multiple articles to one expert. The hypothesis is "do experts think the article is correct", and you test it by find the percentage of experts that think it is/isn't.

What is truly ironic is that while Nature likes to hold itself out as an open source for medical knowledge (and thus more like Wikipedia), it is in fact a gatekeeper of knowledge like Britannica. When Nature publishes an article, the belief of the scientific community is that the article is correct *because it's in Nature*. But Nature is the journal of statistical regression sciences - medicine, global warming, etc., i.e. disciplines where there is no right answer or it's impossible to know the right answer because you are observing only a small percentage of all the variables being affected. It tests associations, not causality.

Keep this in mind when a journal like Nature also makes policy proclamations ("global warming needs to be stopped") or creates artificial hierarchies by its coverage (substantially more articles on HIV than malaria, so HIV becomes more "important" than malaria, etc.)

Score: 15 (15 votes cast)

Score: 15 (15 votes cast)

So Ends The Ochlocracy of Medicine: How To Fix Medicaid, Part 1

Preferred Drug Lists are the bane of the practicing clinician. Instead of, for example, a psychiatrist being allowed to prescribe any antipsychotic they think appropriate, Medicaid requires them to pick from a list of only three, "on formulary" agents.

Unfortunately for doctors, the logic is sound. Unless one can show that, for example, two antipsychotics do not have the same general efficacy or tolerability across a population, than an insurance company cannot be reasonably obligated to provide both, especially if one is cheaper.

Psychiatrists complain that some patients respond better to one drug than another, but while this may be true, there is no way to predict this; try the formulary ones first. But this is just a red herring. What angers doctors is that these restrictions are an intrusion on their practice. Doctors are better able to decide risks and benefits of a medication; which drugs to prescribe, and when.

This would be a great argument if it were true. It isn’t.

The truth is that doctors are woefully ignorant of the available scientific data. As with literature and philosophy, most doctors read about the science, not the actual science itself. In general, doctors prescribe medicines not based on careful review of data, but impulse, habit, and the recommendations of “thought leaders.” (Seriously. They’re actually called that.) Prescribing medicines based on partial information or clinical soundbites may feel like "the art of medicine" but it is, in fact, a random process. It is certainly no better than having an insurance company that did review the data tell you what not to prescribe.

They also tend to practice in a vacuum. A patient’s psychiatrist and cardiologist have no link. Are the treatments synergistic? Antagonistic? Neither fully know that the other is doing.

And so, because doctors are not rigorous about their practice, someone else has to be. One of the most outrageous way psychiatrists, and possibly other physicians, waste money is to use multiple medications for a situation that could well have been handled by one. “Polypharmacy” is so common that it is actually codified in treatment guidelines, despite—and this is where insurance companies go insane—there being practically no evidence that this is ever appropriate. Why combine two antipsychotics when maybe more of one will do? It may seem plausible that two are better than one, but they aren’t. It may be true that a patient needs two drugs; but you can’t assume that. The default practice cannot be augmentation. That has to be the maneuver of last resort.

Loose practice has caused the paradigm shift. It used to be that everyone deferred to the judgment of the wise physician. No more. Now, it’s incumbent upon us to show why we need to use a treatment, not for the insurance company to trust that we know best, that we made a careful analysis of the risks and benefits—because we didn’t. We complain that medicine is being assaulted in a million different ways—insurance companies, lawyers, alternative practitioners—but the reality is it is the exact same assault: we are no longer trusted to know best.

So what to do? There is a solution. But you’re not going to like it.

Link each Medicaid patient with a pharmacy budget per specialty—money controlled by the psychiatrist. A psychiatrist can use any drug, any dose, no restrictions, but only up to, say, $10 a day. Go.

There are numerous advantages.

First, there is cost control.

Second, Pharma will inevitably cut prices in order to compete.

Third, it gives doctors their autonomy.

Fourth: it will force doctors to pay very close attention to what is, actually, best practice. They will have to be more attentive to outcome studies. They will have to predict side effects: if you’ll need to add a second drug to counteract the side effects of the first, it may be better to use a completely different drug.

Fifth: They will use fewer medicines. Two is not always better than one; but it certainly is twice as expensive with twice as many side effects.

Sixth: Pharma no longer has incentive to create “me too” drugs. They are incentivized to come up with novel, even niche, treatments.

If you really want to tax the imagination of doctors, and force a level of rigor in medicine that has not been seen since, well, since never, create a global pharmacy budget per patient across all subspecialties. This way, if a psychiatrist wants to prescribe Zyprexa, he’s going to have to discuss with the cardiologist whether that is more cost effective than the Lipitor. Wow.

The unexpected benefit is that the two doctors have to communicate. Maybe a switch from Zyprexa could preclude the need for Lipitor? Maybe? Hello? Let this communication be billable to Medicaid. $100 per “consultation” is more than offset by the pharmacy savings. There are going to be some patients who actually do require more money, more medications. In that case, the doctor can petition for increased benefits. Doctors hate doing this. Too bad. The problem was created by doctors, not by pharmacists.

Finally, to bring Pharma into the game: the first 30 days of a prescription must be piad for by the Pharma company making the drug, i.e. samples or vouchers. This way, only the drug that actually works gets paid for by Medicaid. That's gold.

It’s worth stating, for the record, that I am opposed to government interference in my practice. I don’t particularly like lawyers, either. But the sad truth is that the state of psychiatry is the fault of psychiatrists, who have failed to take full responsibility for their own education and practice. To blame anyone else at this stage is totally disingenuous.

Score: 9 (13 votes cast)

Score: 9 (13 votes cast)

If France Gets Its Way, 38 Million People Will Die

"All of healthcare is in crisis." Well, Chirac is not helping matters.Healthcare policy has two concurrent and dangerous trends developing. In the first trend, as detailed recently by Dr. Marcia Angell in the New York Review of Books ("The Truth [sic] About Drug Companies") is the pervasive notion that pharmaceuticals are a need and a right, and cannot be left to the drug companies to disburse with an eye to profits. Leading us to the second trend, as evidenced by France's recent swipe at the U.S. for not allowing poor countries to bypass patents and create cheap generic HIV drugs, which specifies that when medical need arises, government should be allowed to commandeer treatments and prices for the good of the people who need the drugs. Looks like the old argument: social justice vs. personal responsibility. Except the argument isn't grounded in reality. Saying something vague like "people need these drugs," misses the immediate point: which drugs? On what grounds is it even possible to say that people "need something" that didn't exist until a company created it? Under what circumstances can we say people now need a drug that won't be invented for another 10 years?

The problem, in part, in this debate arises from scientists confusing discovery or research with invention. Looked at in terms of the production of novel material, certain distinctions can be made. Discovery and research are not creative acts. While they require creative thinking, they do not add anything materially new to the world. Alternatively, invention is the act of creating something that did not exist. There was no Prozac or Tylenol until someone invented it. You may think the rainforests have all the cures, but they don't. As of right now (things could change) the law appreciates this, and only allows for the grant of the patent right when the invention in question is new, useful, and not obvious. However unfair this may seem, that is the system. Ordinarily, no one debates what is new or useful. Obvious, by contrast, is the source of much debate. Can something be not obvious if it was the logical next step? Or if someone else would have done it sooner or later? Many do not understand this debate, lamenting the unfairness of assigning property rights in science "when discoveries that depend on generations of prior science are patented by the person who made the last step."

This is the classic mistake. The last step is not obvious before it is taken. Perhaps there exists an example of a patent in which the inventive step was obvious to everyone before the inventor himself took that step? It seems obvious now for surgeons to wash their hands before operating, but tell me, why wasn't it obvious to the doctors who performed surgery in the hundreds of years before the practice was conceived? It is common in many fields to look at patents and say "oh, I could have thought of that." This is impermissible hindsight, because the determination of obviousness can't be made after the fact.

I suspect, however, that the current debate among politicos over drug patents has little to do with the assignment of property rights (which is best left to lawyers and judges skilled in the practice of assigning rights generally). Rather it is a land grab to curry favor with voters at the expense of the health of future voters. This is what is so damaging about the controversy over HIV drugs. The drugs exist, and they are needed now. But how to hand them out?

Note that the debate is not about changing patent law with respect to future drug patents. Rather, the debate is over changing the laws on existing patents for successful and safe drugs that were developed under the assumption that the patent to them would last 20 years.

This is "patently" unfair, because it amounts to changing the rules after the game has already been won. Drug companies invest hundreds of billions to create (not discover - create) these drugs. Scientists like to dismiss this part of the argument, because they feel that crass commercialism sullies the purity of science. This is as childish as it is preposterous. Scientific research is massively expensive. The investment is made by investors who don't care about science, but do care about returns, based on the understanding that anything they invent they will be able to sell exclusively, at least for a while. To threaten abrogating the patent right for successful drugs, or artificially manipulate their prices will cause investors to pull out of drug companies now and into more predictable and less regulated industries. This will reduce the investment in future drugs. You don't appreciate the strategic problem here, because the future drugs that will never get invented don't exist, so it does not seem like you are losing anything.

But you are.

If you do not think that this is true, consider the fact that many of the newest drugs are cosmetic or lifestyle drugs, like Viagra et al, or are "me-too drugs" (other versions of the same kind of drug, i.e. 5 different Prozac like drugs.) Drugs which treat conditions that are not life-threatening and which are therefore not prone to federal or HMO price control. Compare this to the fact that drug companies invest comparatively little in new antibiotic research to combat the well-known problem of drug resistant bacterial strains. Public and social policy has distorted the market and predictability of patent rights, so drug companies stay away from research that is likely to become a political issue. Why bother investing to invent an antibiotic (or HIV drugs) when it could be commandeered by the government because it is "needed?" And the public suffers. It is convenient for France to demand the commandeering of the patent to HIV drugs to allow for cheaper generics. But current HIV drugs are not curative. Who, exactly, does France expect to invent the actual cure--- that will then likewise be commandeered? In a flashback from the Fountainhead, France wants to take credit for charity that someone else will pay for.

Would you rather have Viagra or a new HIV vaccine? Both are a question of money, but if you are going to place a value judgment on one over the other, then you have to incentivize the drug companies to do what you want. At the very least, you shouldn't disincentivize them.

Good drugs cost a lot, and we are going to have to pay it. Period. Because the alternatives are completely unfathomable: that good drugs are never invented; or, that they are invented but kept secret. Maybe they are used only to cure members of one's family, or race, or class, or religion. That is perfectly legal, by the way. France should think about this before they sentence millions to death.

Score: 20 (22 votes cast)

Score: 20 (22 votes cast)

For more articles check out the Archives Web page ››