Clinical

First Anniversary Of The Death Of Antidepressants

Continue reading:

"First Anniversary Of The Death Of Antidepressants" ››

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Yet Another Study On Antidepressants, And No One Notices The Timing

Continue reading:

"Yet Another Study On Antidepressants, And No One Notices The Timing" ››

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

ECT Deserves A Press Release

This Is What You Wanted, Right?

Continue reading:

"This Is What You Wanted, Right?" ››

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

An Addendum To "Ten Things Wrong With Medical Journals"

I added another "thing wrong" with medical journals. At the bottom. I think it's worth reading.

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Ten Things Wrong With Medical Journals

I know, right? Only ten?

Continue reading:

"Ten Things Wrong With Medical Journals" ››

Score: 11 (11 votes cast)

Score: 11 (11 votes cast)

Will Lilly's New Glutamate Agonist Antipsychotic Be A Blockbuster?

Continue reading:

"Will Lilly's New Glutamate Agonist Antipsychotic Be A Blockbuster?" ››

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Number Needed To Treat

How a relatively unused metric can help you score chicks at the Limelight.

That's right, I said score chicks. You got a problem with that?

Continue reading:

"Number Needed To Treat" ››

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

How To Take Ritalin Correctly

Continue reading:

"How To Take Ritalin Correctly" ››

Score: 81 (93 votes cast)

Score: 81 (93 votes cast)

How Do You Treat Atrial Fibrillation?

Continue reading:

"How Do You Treat Atrial Fibrillation?" ››

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

No, Not Effexor, Too!? The Most Important Article On Psychiatry You'll Ever Read, Part II

In which Anne Neville agrees to believe pretty much anything anyone ever tells her, ever, and Richard discovers people are gullible idiots.

Continue reading:

"No, Not Effexor, Too!? The Most Important Article On Psychiatry You'll Ever Read, Part II" ››

Score: 19 (21 votes cast)

Score: 19 (21 votes cast)

The Most Important Article On Psychiatry You Will Ever Read

I'm warning you.

Continue reading:

"The Most Important Article On Psychiatry You Will Ever Read" ››

Score: 73 (73 votes cast)

Score: 73 (73 votes cast)

Schizophrenia and Dry Cleaning?

A reader (who wants me to write an article on autism and paternal age-- I swear I'm getting to it) sent me a reference to a 2007 article finding an increased rate of schizophrenia in those born to parents who were dry cleaners (all Jewish, negating a racial association). The authors speculate it's tetrachloroethylene exposure.

There were 4 cases of schizophrenia, out of 144 dry cleaning families. What's interesting is that in 3 of the schizophrenia cases, the father was the dry cleaner.

How does it happen? There are two possibilities: one is that tetrachloroethylene is neurotoxic in developing fetuses, so the dad must have somehow brought it home with him to the pregnant mom. Or, it affects male sperm/ germ cells.

As for Cho, I don't know if his parents were dry cleaners in Korea, or if they started when they all came to the U.S. But something worth investigating.

BTW: not that this would excuse him even if it were true.

To Leslie, the reader: if you want credit, put in a comment and I'll put your contact info up here.)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Pathological Liars

So you think you might be dating a pathological liar? No, you're not. He's just a big jerk.

The popular stereotype of a pathological liar-- a chronic liar, deceiver, who lies to get out of things, or into things; who tries to con you into something, or control you; who cheats on you and then denies it, makes up stories about where he was-- all this is wrong. It's malingering, but it isn't pathological lying. He's a tool, but he's not psychiatric.

"Pathological lying" is often interchanged with "pseudologia fantastica." (NB: many psychiatrists use pseudologia fantastica interchangably with confabulation-- this is also wrong, as will be described below.) Pathological lying was originally defined as complex lies which are internally consistent, that may drag on for years and-- and this is the key point-- do not have an obvious purpose or gain. They're not trying to con you into or out of anything. They're just making crap up.

The lies are unplanned, spontaneous. Once told, they generally stick (for years)-- but it's fair to say the pathological liar doesn't know what he's going to say until he says it. He is a bullshit artist who makes it up as he goes along, and who then semi-believes his own crap.

And the lies aren't even useful lies. You ask him what he did last Saturday and he tells you he went to the museum; and maybe he says at the museum he saw a guy try to rob the gift shop, but he got caught by two off duty cops wearing blue hats. And later you learn he was really at a movie with his girlfriend and you think, why the hell did this freak make all that up?

That's why it's called pathological.

A pathological liar is like a 4 year old kid, who tells you what happened to him down by the lake. Meanwhile, there's no lake.

The important question here is this: does the pathological liar know he is lying? Or does he believe his stories? Is he lying, or is he delusional?

The answer is: both. Sort of.

He is not delusional, but he hovers in that half-world of the narcissist (oh, there's that tie-in), where the lies are believed until he gets caught, but then-- and this is the move that only a few can pull off-- he acknowledges that the "facts" are lies, but not the essence, the spirit. "Ok, look, I'm not really in the CIA." But in his mind, he knows that if conditions were right-- if something big went down-- he could be exactly like a CIA agent, and that's close enough. If he saw a suicide bomber, he'd be able to movie- kung fu him, grab the Sig Sauer and squeeze off a few rounds. He also knows which wire to clip. How does he know? Because he's in the CIA.

If aliens actually did come and attack us, he knows he would actually be able to fly a spaceship.

Pathological lying is not "confabulation." In both cases, lies are told spontaneously and freely, without clear intent, purpose, or gain-- except that in confabulation, the reason the person lies is to fill in the deficits in his memory; he can't remember what actually happened. Hence confabulation is associated with dementia ("when I was 18 I went to Paris with my unit and I saw... 8 puppies get eaten by Chamberlain and de Gaulle-- hand to God I saw it"), and especially with alcoholic dementia/hallucinosis ("I don't know what happened to me-- six guys jumped me... yeah... six... Canadian guys, I think they were Satanists, no, wait, Stalinists, yeah, that's right, and they could read my mind...")

What about biological correlates? There aren't any, because this isn't a disease, it's a description. Here's an example: an article entitled, "Prefrontal white matter in pathological liars" found massively (20%+) increased prefrontal white matter, and a 40% decrease grey/white matter ratio in pathological liars, as compared to both controls and antisocials. But before you crack an anatomy book to figure out what that means (more prefrontal white matter= more ability to think and reason), you should know that the subjects they labeled "pathological liars" were really people who purposely and frequently lie to get a gain-- in other words, they were big fat evil scumbag liars, but not pathological liars. What this study found was that people who frequently lie develop a better brain for manipulating information, remembering stories, etc-- which is interesting, but not all that surprising.

My take is that pathological lying is a disorder of identity; the person imagines for himself an separate identity, and then fantasizes experiences and events which may be otherwise ordinary and predictable-- he went to the museum-- but in his mind happen only to "that" person. The lies hold the clues to that identity, but they may not be obvious. For example, maybe the part of the lie that's important isn't that he saw a guy rob the gift shop and get arrested, but that he was at the museum by himself-- the point is that he imagines himself a loner, or an artsy type, etc. Or maybe he's sees himself living in a world where crimes happen frequently. And maybe he thinks he's a superhero.

The pathological liar doesn't place much value in experience; it's all in identification. He doesn't need to be in the military to know exactly what it's like, because he's watched enough war movies (e.g. one) or read Tom Clancy. (Aside: that's the huge appeal of Clancy and Crichton-- enough detail to make you think you know the inner workings of the professions they describe.) It's wrong to dismiss the lies as valueless; like Zelig, these people do have an intuitive grasp of the relevant thought process, emotions, affects, and even consequences of the experiences they describe. They're just made up. So when he gets caught in his lie, he secretly blames the other person for not appreciating that whether it's a lie or not is trivial, irrelevant; it still affected him just the same.

------------------

(It would be interesting to study whether (true) pathological liars are able to provide a better "profile" of criminals, heads of state, etc, than professional profilers, and what supplementary factors might improve the accuracy of the profile. ("Here are some videos/documents on Vladimir Putin. Tell us what you think. Then, go out to dinner with this beautiful blonde ex-FSB agent and see if you come up with any further insights.") I suspect also that pathological liars would more predictably pass the new fMRI lie detectors; these detect binary lies ("are you this or are you not this?") but pathological liars hold contradictory truths simultaneously and thus may not register as deceptive. (P.S. I think I know how the test procedure can be altered to pick this up; but I also think I know how these tests can be reliably beaten. If anyone wants to study this, let me know.))

Score: 13 (17 votes cast)

Score: 13 (17 votes cast)

Pediatric Bipolar. Yeah. Okay.

Rebecca Riley is the 4 year old who died of psychiatric drug overdose-- she was on 3 of them-- supposedly with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. If you want the scoop from a psychiatric perspective, you should read this post from the resident blogger (no pun intended) at intueri.

But I'll add two things. Let me be very clear: it is not unlikely a 4 year old has bipolar-- it is absolutely impossible. This is because bipolar disorder is not a specific disease with specific pathology that one can have or not have; it is a description of symptoms that fall together. We decide to call a group of behaviors bipolar disorder-- and meds can help them, for sure-- but this decision is completely dependent on the context of the symptoms. Being four necessarily removes you from the appropriate context, in the same way as having bipolar symptoms during, say, a war, also excludes you from the context. You might still have bipolar, but you can't use those symptoms during the battle as indicative of it. If I transplant you to Brazil, and you can't read Portugese, does that make you an idiot?

I don't mean that 4 year olds can't have psychiatric symptoms. I'm saying you must be more thorough, more attentive to the environment. As soon as a person-- a kid-- is given a diagnosis, it automatically opens the flood gates for bad practice that is thought to be evidence based. That's what makes the diagnosis so dangerous. Instead of, "should I use Depakote in this kid?" it becomes "It's bipolar, so therefore I can use Depakote."

Secondly, we must all stop saying these drugs are not indicated for kids. That's meaningless. We can debate whether they should be used or not in kids, but you can't say they shouldn't be used because they're not indicated. To quote myself (lo, the narcissism):

Thus, categorizing a medication based on an arbitrary selection of invented indications to pursue—and then restricting its use elsewhere—may not only be bad practice, it may be outright immoral.

I do not make the accusation lightly. Consider the problem of antipsychotics for children. It is an indisputable fact that some kids respond to antipsychotics. They are not indicated in kids. But don’t think for a minute there will be any new antipsychotics indicated for kids. Who, exactly, will pursue the two double blind, placebo controlled studies necessary to get the indication? No drug company would ever assume the massive risk of such a study-- let alone two-- in kids.

And which parents will permit their child in an experimental protocol of a “toxic” antipsychotic? Rich parents? No way. The burden of testing will be undoubtedly born by the poor—and thus will come the social and racial implications of testing on poor minorities. Pharma is loathed by the public and doctors alike, and the market for the drugs in kids is (let’s face it) is effectively already penetrated. There will not be any new pediatric indications for psych meds. Not in this climate. Think this hurts Pharma? It's the kids that suffer.

It's funny how psychiatry always tries to appeal to a higher authority (FDA, "studies", clinical guidelines, thought leaders, etc) except when it gets in trouble. And then it's always the same refrain: "no one can tell me how to practice medicine."

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Geodon Is Not BID

If one more person tells me Geodon "doesn't do anything," I'm going to choke them with the capsules. If it's never worked in your practice, how do you explain the numerous efficacy studies? All flukes? All of them? It couldn't be you?

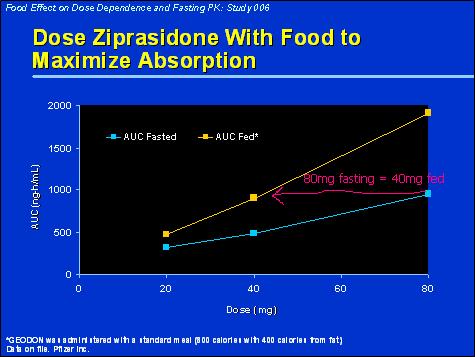

Probably everyone has heard Geodon must be taken with food. But that's not to prevent nausea or protect the stomach lining, it's to get the drug to be absorbed.

You'll have to take my word for it right now that 120mg is the a base dose. (120mg Geodon=10mg Zyprexa=3mg Risperdal.) This is amazingly hard for psychiatrists to appreciate ("there are equivalences? And those are the doses??") But it's even harder to get them to understand the relationship to food: Geodon needs fat to be absorbed.

80mg on an empty stomach (blue line) gets you the equivalent of 40mg if taken with food. That's half the dose. In other words, if you dose your Geodon "all at night" (no food) then you're getting about half of what you thought you were. (In chronic dosing this will be less of a problem, but 30-50% increased absorption with food is a good guideline.)

Hospitals: they dose BID, which means morning and night, which means no food either time. Guess what happens (or doesn't).

BTW, crackers won't do it. The graph above is with 800 calories, 400 calories of fat. That's a meal, not juice.

If your doctor gives you less than 120mg and then gives up, he doesn't understand the proper dosing of Geodon. If he doesn't know about the importance of food, then you're in big trouble. Forget about reading journals, he's not even listening to the reps. (I know: because they're biased.)

I bring this up partly as a public service message, but also to explore the curious observation that even though many doctors know this already, they still don't dose with food. I can't imagine laziness is the answer. There is some weird thinking that this isn't relevant in the "real world" because food is weaker than medication. Drug-drug interactions matter; drug-food couldn't be important. And if it was really important, someone e would have mentioned it.

Everyone complains about diabetes and weight gain; here's a drug that likely doesn't have these problems. But because it doesn't have those toxicities, it therefore can't be "strong," or effective.

I'm not trying to advocate for Geodon. I'm pointing out that much of our perception of a treatment's efficacy can come simply from our mishandling of it; and to alert humanity to the inherent bias in ourselves. If we've never gotten Geodon to work, then not only do we think it doesn't work, but we think everyone who says it does work is a Pfizer schill.

Seroquel had this problem, too. Six years ago, no one used Seroquel. Now everyone uses it. Did they improve it? No. It's marketing, but in reverse: Astra Zeneca didn't delude everyone into thinking it works when it doesn't; we deluded ourselves into thinking it didn't, when it did. So whose fault is that? Depakote: six years ago Depakote was untouchable, it was the king of bipolar treatment. Now? Did we get new data saying don't bother? Did they make the drug weaker? This is the key: the data that brings us today's conclusions is the exact same data that gave us the past's, opposite, conclusions. In other words, no one actually read the data; they based their conclusions on something else. Clinical experience? No.

The bias goes well beyond "Pfizer paid that doctor off"-- it comes from a belief system ("meds are life savers" vs. "meds are band-aids"; nature vs. nurture; your own race/gender; your family history of mental illness/drug abuse (or lack of it); your desire to be a "real doctor" etc, etc) that is much deeper and exerts a much stronger control over your thinking. To the exclusion of any new information.

And, of course, it's so much a part of you that you don't see it as a bias. And other people (patients) don't know it's there, so they're at the mercy of your unexamined assumptions.

The solution is exhausting, and no one will like it: constant critical re-evaluation of your beliefs. Both the science (as much of it as there is) and countertransference. And, most importantly, long looks at your own identity. How did you come up with it? Because, in fact, you did.

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

When Your Patient's Parent Is A Psychiatrist and A Patient and You Just Want To Go To Bed

If you want to test the faith of a psychiatrist in their "science", present them with one of their own.

In my career I have treated a few dozen children/spouses of doctors, and about a dozen of psychiatrists. Treating patients with these connections is difficult, if we are to be honest, for two reasons: 1) a lot of the trickery and hand waving we use on regular patients won't work with them, because they know the game. 2) we feel tremendous pressure to do a good job, because we feel that we are being graded.

The result is we almost always do an inferior job. Notwithstanding the admonition against treating family, the reality is that if they knew what to do, they wouldn't be referring them to you. And the trickery and bs are vital parts of the dance: these say you have really no idea why this works, but you're optimistic, so you are offering a framework to think about how it could work. The framework doesn't have to be "true"-- it has to be internally consistent.

But the countertransference towards the patient and his family is so strong that we do things we should not, think things we should not.

Treatment is even harder when both the patient's psychiatrist-parent/spouse is also a psychiatric patient somewhere. If you want to see an entire department blow an aneurysm simultaneously, say, "I'm getting X as a patient, and X's mom is a psychiatrist-- and a patient in the Bipolar clinic!"

In any other scenario, a mom in the bipolar clinic would suggest that the child had a similar disorder, by virtue of being a first degree relative. But in these cases, psychiatrists read it differently: it means the mom made the kid insane. It was the mom's fault. Not genetics, or biology, or even shared environment: specifically bad parenting. And not bipolar-- personality disorder.

I can make a statement that is completely unqualified, without exception: never, not once, has anyone hearing of this scenario said to me something like, "bipolar in educated families is difficult to treat." In every case, again without exception, every single person who has heard of the situation has said the same exact thing: "Oh my God, she's a borderline, and the mom is even more crazy."

What's interesting about this, to me, is two things. First, how immediate, reflexive, and certain everyone is of this assessment-- given even before they ever see the patient, only hearing that the mother of a patient is a psychiatrist. "Mom's a psychiatrist..." Boom. Case closed. Out the window goes diagnosis, biology, serotonin, kindling, TSH, whatever-- it is immediately predicted to be personality disorder due to an unhealthy relationship between parent and child (or spouses). Overinvolved, underinvolved, abusive, manipulative, whatever.

Medications are inevitably thought of as band-aids-- likely to be changed thousands of times over the lifetime-- or proxies for therapeutic maneuvers ("I will nurture you by giving you extra Klonopin to get you through the holidays, but then I will be a disciplined parent-surrogate and reduce it in January.") A family history of CNS lymphoma is less telling than a Dad who is a psychoanalyst. The adult child is crazy because the parents made him crazy.

That's the first thing. The second thing is this: they are almost always right.

More in next post.

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Competency To Commit Suicide?

Continue reading:

"Competency To Commit Suicide?" ››

Score: 3 (5 votes cast)

Score: 3 (5 votes cast)

More on Medical Competency

The primary rebuttal to my thesis of personal autonomy is, "well, we doctors are just trying to do what's best for the patient." This is categorically false (words chosen carefully.) What they want is what's best for that particular medical issue because it leads to the betterment of the patient; but this is not the same as taking the patient's life in total and deciding what is best overall for their lives. What the patient wants in their lives may be, to them, worth the risk.

And I'm not saying the doctors aren't trying to do what they think is best; but you don't think George Bush, et al, are doing "what they think is best" for us? (Before you give a reflexive answer, grow up.) Allowing doctors extraodinary powers to treat against one's will is no different than executive privilege, an example chosen carefully because it highlights the political/societal nature of the process, over the scientific.

Continue reading:

"More on Medical Competency" ››

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Not Competent To Make Medical Decisions?

As a forensic psychiatrist, I am often called to evaluate someone for their "competency"-- to make medical decisions, to make financial decisions, to stand trial, and (theoretically) even to be executed.

In these various consults, the basic question is this: are they so impaired, that they don't understand the relevant issues and can't make rational decisions?

Many psychiatrists find this complicated and time consuming work, because they focus on the nuances of the patient's symptomatology and illness. They try to get extensive past histories, corroborating information, etc, etc. All this is important, but they miss the forest for the trees.

Now this is, of course, only my opinion. But it's important that you hear this opinion, because I am, apparently, the only person who has it, so you won't hear it anywhere else.

The truth to competency evaluations is this: the patient is the least important factor.

Continue reading:

"Not Competent To Make Medical Decisions?" ››

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

For more articles check out the Archives Web page ››