Legal Issues

"Pivotal Role That Psychiatry Has Come To Play"

They are also the main educators in the field. Which is unfortunate. Not because they're bad, but because they are part of that system they are teaching. All they can tell you is what it's like inside the building. Not whether the building is, in fact, a boat, or a duck, or dream.

Continue reading:

""Pivotal Role That Psychiatry Has Come To Play"" ››

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

The Question Isn't Why Do Babies Do It

(From Nature)

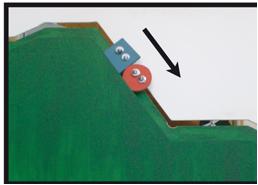

The experiment is to grab a bunch of 6 month old and 12 month old babies, and show them a little wooden shape with eyes glued onto it climbing a hill. Then, while a shape is climbing the hill, another shape either comes up behind it and pushes it upwards ("helps"), or a shape comes from above and pushes it downwards ("hinders.")

They then allowed the infants to reach for either the "helper" or the "hinderer."

Continue reading:

"The Question Isn't Why Do Babies Do It" ››

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Score: 5 (5 votes cast)

Is Taking Nothing Legal?

If Provigil has any effect on a specific athlete's physical performance beyond keeping them awake, I'd argue it was placebo effect. So a drug with a placebo effect is illegal. Fine.

But what about the reverse situation: what about giving an actual placebo to an athlete, and telling them it's oh, I don't know, growth hormone? Or Ritalin?

Continue reading:

"Is Taking Nothing Legal?" ››

Score: 3 (3 votes cast)

Score: 3 (3 votes cast)

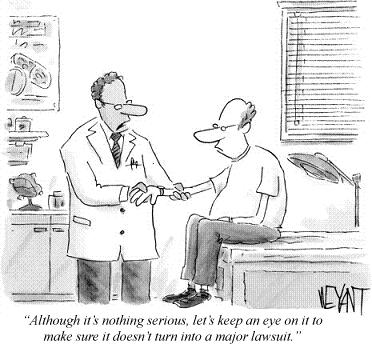

Why Is This Funny?

Because it's true.

Is the thing going to be serious, or not? If you think not, then monitoring it won't make any difference because it won't be serious. If you think it could be serious, then you should be monitoring it whether or not there are lawyers in the world. Are you saying that the only reason you would take this thing seriously is because of lawyers? Then thank God there are lawyers.

If you blow it off and it turns out to be serious, then you made a mistake, you were wrong. Then becomes the question of whether you were negligent. Would others in your profession have also blown it off? If so, then it wasn't negligence.

Doctors often think that if they don't do something- a test, document a finding, etc-- they'll get sued. "I have to check the level." "I have to document "no suicidality."" "I have do an AIMS test." "I have to give him a copy of the PI." The reason is "I'll get sued if I don't."

But lawyers can't sue you for not doing these things. They only sue you when something bad happens. If nothing bad happens, you could be drawing penguins in your chart, lawyers will never know.

Forget about lawyers. Be a doctor: do you need to check that thing, or not?

If your clinical behavior is significantly different because of the existence of lawyers, you need a massive overhaul of your thinking and practice. You have lost your way. And patients will suffer.

(See #4.)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Child Rapist-Murderer John Couey Loses By Eight

Here's an example of what I've been talking about.

I'll spare you the details, but John Couey is found guilty of kidnapping, raping, then burying alive, 9 year old Jessica Lunsford. Here's the part relevant to our disussion: defense attoneys said Couey could not be executed because he was mentally retarded-- his IQ was tested by the defense at 64. (They even let him color with crayons during trial.)

But, and I'm quoting:

Circuit Judge Ric Howard in Citrus County ruled that the most credible intelligence exam rated Couey's IQ at 78, slightly above the 70 level generally considered retarded.

That's it, people. 8 points. We may not agree whether the death penalty is good or bad, but can we at least agree that decisions of life or death shouldn't come down to, well, how stupid you are?

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Lawsuit Funding

Sponsored post: as many bloggers are, I was offered $30 to review someone else's site/product. Ordinarily I pass, but this one caught my eye for reasons which will become clear.

Continue reading:

"Lawsuit Funding" ››

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Damned If You Do... No, That's All. Damned If You Do.

In case there was any doubt that psychiatry is on the march (from Psychiatric Times June 2007):

The mass murders at Virginia Tech [sic: there was only one mass murder] could lead to harsher laws restricting [mentally ill people's] rights... Perlin, professor of law at NYU, predicted that several states will try to change the basis for involuntary commitment from danger of harm to self and/or others to the need for psychiatric treatment. [emphasis mine, but really, does it need emphasis?]

Mr. Perlin said he expects the U.S. Supreme Court will be asked to rule on such a statute's constitutionality within 10 years. "I am already counting the votes."

Me, too: Scalia, Thomas, Roberts, Alito, Ginsburg-- strange bedfellows, indeed, but Scalia and Ginsburg spend every New Year's Eve together-- against; Souter, Kennedy for; the rest is anyone's guess (Stevens may not even be there.)

The second article, from the same issue, accidentally describes the crux of the psychiatry/violence dichotomy. In "Mental Health Staff Can't Sue If Injured By Patient," the writer explains how it is rare, and generally discouraged, for staff to sue or press charges against a patient who is violent and injures them.

Patients who attack mental health professionals in hospital settings are rarely prosecuted and usually cannot be sued for civil damages [said] Ralph Slovenko, Ph.D. at the annual meeting of the American College of Forensic Psychiatry.

...Authorities usually take the position that it would be inconsistent to prosecute a person who has already been hospitalized for reason of mental illness...

... a New Jersey Court ruled [that] to convict a mentally ill person for displaying symptoms of mental illness... could not be justified constitutionally or morally.

Anyone disagree? Choose carefully. Here's the problem: the exemption from prosecution isn't for the insane behaving insanely, or the schizophrenic exhibiting psychosis; the exemption is for any patient. "Patient" in this context, is defined as anyone who is in the psychiatric hospital. In other words, it's not a label based on pathology; it's a label based on geography.

This may surprise many people, but psychiatrists hospitalize non-mentally ill people all the time. Any resident will lament how often they are confronted with the malingering drug user who fakes suicidality to gain admission. Well, if you admit him-- strike that, if he has ever been admitted-- then he is a de facto patient. If he kills you, he is automatically in a different legal status than if he murdered you in a supermarket. For example: no death penalty.

It goes without saying, of course, that even the presence of mental illness shouldn't free one from prosecution. That's why we have the legal construct of insanity.

Here's the clincher:

The situation is analogous to the "Fireman's Rule" in tort law, he said. A firefighter... cannot sue the owner of a burning building for injuries sustained in firefighting.

... I assume because a firefighter must have a reasonable expectation of fire-related danger. Fine. But if the firefighter, while fighting the fire, gets shot in the face by one of the meth-lab workers inside that the owner of the building is employing to make methamphetamine, is there no basis for a suit? Does reasonable expectation of a certain level of danger extend to, well, to volitional acts of violence that have nothing to do with the physical structure that the violence happens in?

The reason I mention these two articles together is because they are the same. "Mental illness" is a term so vague and empty that it is dangerously useless. Reducing one's responsibility, or restricting their freedom, based on such an arbitrary term is, well, insane. Doing both at the same time is a tacit acceptance of classism; that some have the responsibility to rule, and some have the responsibility to be ruled.

Oh, I know: everyone hates George Bush because he has no respect for civil liberties. Ok.

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Dr. Nasrallah Asks Questions That No One, Including He, Wants Answered

But I'm going to try.

His editorial appears in the journal Current Psychiatry, of which he is the editor. I respectfully disagree.

Continue reading:

"Dr. Nasrallah Asks Questions That No One, Including He, Wants Answered" ››

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

Score: 1 (1 votes cast)

FTAC: Forensics Gone Awry, And I told You So

Following from my premise that the erosion of civil liberties and descent into fedualism necessarily coincides with the rise of psychiatry, I found a short article in the Economist, the magazine of record of the Whig Party, which explains that British Government runs a "Fixated Threat Assessment Centre," i.e. capturing stalkers. It has 4 cops, and a forensic psychiatrist and psychologist.

You probably think that the shrinks are "profilers." Maybe they are. But their real value is in their power to do what cops can't: involuntarily commit people who they feel are dangerous. Quoting the Economist:

The Met [cops] defines its [suspects] as those who are "abnormally preoccupied with certain ideas or people." The inclusion of "ideas" gives it wide remit. Could those abnormally pre-occupied with the idea of jihad-- or, indeed, human rights-- be considered fixated individuals?

Disclosure: I actually think this is clever-- why not tap the legal resources of psychiatrists to help catch bad guys? But that's exactly the point: no one should have the ability to use that power extra-psychiatrically. It's seductive and it has no recourse for appeal, no controls.

The article goes on to state the FTAC has been operating for 8 months with no official announcement; it won't say how many people it has caught or tried; and, of course, it can't, because of confidentiality of the "patients."

Good luck, everybody.

Score: 3 (3 votes cast)

Score: 3 (3 votes cast)

Paris Hilton or Mary Winkler? Forensics Gone Awry

I'll take Paris any day.

So Paris goes back to jail after the behind the scenes/cover of darkness/MK-ULTRA deal she made to get out of jail early was met by the public with consternation.

As near as I can tell, a/her private psychiatrist (his blog here-- mine's better, dammit) visited her for two hours in jail, then made a plea to the sheriff that serving her sentence in jail was psychiatrically harmful to her. So they let her out to serve it at home.

The argument here, of course, is that this is rich-white-girl gets special treatment; and the easiest way to do it is to use psychiatry. And people say, "see? This is they type of abuse we can expect if psychiatry is allowed to influence legal matters."

Fair enough. I don't know Hilton's case, whether it was a appropriate or not, I don't know Dr. Sophy; all I can say is, yes, the potential for abuse exists, but perhaps it is balanced out by the cases in which it is helpful to society.

But consider the reverse situation, and read it carefully because then I'm going to punch someone:

SELMER, Tennessee (AP) -- A woman who killed her preacher husband with a shotgun blast to the back as he lay in bed was sentenced Friday to three years in prison, but she may end up serving only 60 days in a mental hospital.

Mary Winkler must serve 210 days of her sentence before she can be released on probation, but she gets credit for the five months she has already spent in jail, Judge Weber McCraw said.

That leaves only two months, and McCraw said up to 60 days of the sentence could be served in a facility where she could receive mental health treatment. That means Winkler may not serve any significant time in prison.

Same gripe: look how people use psychiatry to manipulate the legal system-- "only two months for killing someone?!" and while I agree that's pretty pathetic, what's worrying me is this: who the hell spends five months in jail without getting a trial?

This probably didn't occur to you, and that's why it still happens. If I kill my preacher husband, I have the right to a speedy trial. If I can't get a speedy trial, I get to pay a fee to be released, and then show up in court when the government gets their act together. But what if I don't have bail money? How can the courts justify indefinite incarceration in the absence of a trial?

Enter psychiatry. You get a psychiatrist to evaluate the person and determine that he is not competent to stand trial. They recommend 60 days involuntary commitment/treatment in a psych hospital in order to "restore them to competency." If at the end of 60 days the evaluator comes back, and if he still thinks they're not competent-- they get (re)committed again. Etc.

But in the vast majority of cases I have been involved in, the report really only reflects the presence of a mental illness, not its impact to the case. As if it is de facto proof of incompetency. It's not.

But here's the move: the "psych hospital" they get involuntarily committed to is actually their cell.

Technically, they are supposed to be committed to an inpatient hospital. Many jails have them on the premises. But if the commitment is for 60 days, and the psychiatrist treating them (i.e. not the evaluator) thinks they are cured, then they get sent back into population (their cell). Maybe they continue on medication; maybe they see the psychiatrist weekly for "outpatient" visits.

Or maybe, maybe, the treating psychiatrist doesn't think they need any treatment. So they spend their commitment in exactly the place they started.

Worse, much worse, is how many people I see that I say are competent and still wind up recommitted for two months. Six months. A year. Think I'm kidding? It is impossible to even estimate how many charts I have read that indicate no psychiatric contact-- not medication, not therapy, not psychiatrist-- for the entire duration of their commitment. And why should there be? The treating psychiatrist doesn't see anything to treat.

You're probably thinking about murderers and rapists; but the majority of these cases are theft, assaults, drug possessions. Can anyone explain to me what possible justification exists for locking up a guy charged with possession for eight months, no trial? And I'll pretend the guy is whacked out of his nut psychotic. Ok? Any justification at all?

I'm not saying you can't sentence him to eight months-- cane him, for all I care; I'm saying you can't jail him for eight months without a trial. Is anyone listening to me?

The system is designed with simply one outcome in mind: keep the poor with high recidivism rates and minimal social resources in jail-- a sort of half-way house for the disenfranchised-- until you can't possibly justify it any longer, and then give them a quick trial, accept the guilty plea ("what guilty plea?") and sentence them to time served and probation-- where you can add further controls.

It's debatable whether keeping potential terrorists in Cuba is a good idea. But when the State starts using pyschiatry to manage their population...

I know you think I am exaggerrating. I'll bet you're not poor.

Score: 7 (7 votes cast)

Score: 7 (7 votes cast)

A Primer on Pedophilia

Continue reading:

"A Primer on Pedophilia" ››

Score: 15 (21 votes cast)

Score: 15 (21 votes cast)

Here's What Governor Spitzer Should Do With The Pedophiles: Send Them To Cuba

So Spitzer, et al have passed a law that allows courts to involuntarily commit sex offenders to psychiatric hospitals until they are "no longer" dangerous-- even if they have not actually committed a crime, or have served their sentence.

Said Spitzer:

"...protecting the public from those individuals whose mental abnormalities cause them to make sexual attacks on others."

"Mental abnormalities?" That they are bad people I can see; but what, precisely, is the nature of this mental abnormality? And it "causes" violence? Causes?

The ACLU of course opposes such an obvious violation of civil liberties-- but they make the same mistake:

"...locking someone up indefinitely because he has a mental abnormality and may commit a crime in the future creates a constitutional nightmare," said Bob Perry of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

"...because he has a mental abnormality." Why the qualification? Is that relevant? And why does everyone agree that there is a "mental abnormality?"

Blame Kansas v. Hendricks, the 1997 decision in which it was decided that dangerousness + a "mental abnormality" is sufficient to involuntarily commit someone (in that case, a violent pedophile) indefinitely-- even after he has already served his sentence. Here's the trick: there would be no other justification for this violation of substantive due process except some mental abnormality that forces you to do things. The only way we can justify indefinitely locking up pedophiles is to call them psychiatric patients.

What's a "mental abnormality," exactly? The Court left the definition up to the states, but it suggests some dangerous synonyms, like "personality disorder."

Here's another: mental retardation. Is mental retardation-- now a exclusion for execution-- sufficient for indefinite civil commitment? They're not going to get better, are they?

There are two main problems with this law. The first is constitutional: you simply cannot lock up a person, indefinitely, unless they committed a crime.

Exactly what is the difference between the Guantanamo terror suspects and pedophiles incarcerated further after their sentence has been completed? Both are being held under the (likely accurate) presumption they're going to cause trouble in the future. Both are driven by an inner and virtually unalterable desperation to commit their respective offenses. Hell, you can even use the same battery of questions to screen for both ("God has given you an odd gift: a schoolbus full of docile 8 year olds. What do you do?") And both are equally explained and treated by modern medicine and psychiatry (i.e. not at all.)

At least the Guantanamo detainees are not U.S. citizens-- they are not entitled to our constitutional rights. For better or worse, American pedophiles are.

If you are against one, you're against both. They're the same.

The law's second problem is social and categorical: these laws interpret certain violent behaviors as psychiatric in nature, without any scientific or even descriptive basis. In other words, it medicalizes behavior simply because it does not know what else to do with it. It says, "only someone whacked out of their skull would be a pedophile."

And some will say, and what do you expect from a culture that so sexualizes youth? Actually, humanity has been sexualizing its youth for thousands of years; it's only in modern times that we've placed an absolute prohibition on acting on it. As I recall, teens getting married was the norm in the Renaissance; the ancient Greeks had institutionalized a form of pederasty-for-education trade.

I bring this up not to justify having sex with kids (duh), but to show that it is quite obviously not a psychiatric disorder. It is a crime that you choose to commit.

There is too much emotion around sexual predators, and it confuses the issues. For example, why do we register them? We don't register serial killers, con artists, unabombers, etc. The argument, "well, wouldn't you want to know if a sex offender was living in your neighborhood?" isn't valid: I assume everyone is a sex offender. Seriously. Especially around my kids. And wouldn't you want to know the Zodiac killer moved in?

Don't misinterpret my support of civil liberties as permissiveness; if you're really worried that a sex offender will offend again, make his criminal sentence longer, harsher. If society wants to make pedophilia a capital offense, fine. But for the love of God, don't turn sex offenders over to the psychiatrists, the two have nothing to do with each other. You may as well send them to the sociologists, they have about as much to do with them.

This is an extremely bad law, and by bad I mean bad for everyone except the bad guys. It sets up the argument that certain "behaviors" are so a part of one's identity that they cannot be altered or prevented, and therefore culpability is reduced while dangerousness is magnified. It allows the government yet another avenue to lock people up without crime. And worst of all, the penultimate decision about who should be locked up for society's benefit is made by the absolute worst group to make this decision: psychiatrists. Psychiatry becomes a tool of the state.

The last major country that ran this way was the USSR. But things are different now, I know. I know.

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Atkins v. Virgina and the Execution of the Mentally Retarded

Once again, I appear to be all alone.

...Because of their disabilities in areas of reasoning, judgment, and control of their impulses, however, [the mentally retarded] do not act with the level of moral culpability that characterizes the most serious adult criminal conduct... [over the past 13 years the] American public, legislators, scholars, and judges have deliberated over the question whether the death penalty should ever be imposed on a mentally retarded criminal. The consensus reflected in those deliberations informs our answer...

So opens Atkins v. Virginia, as opined by Justice Stevens.

It seems unassailable that the mentally retarded should not be executed. Justice Stevens spoke of a consensus; the APA's amicus brief to the Court stated:

(1) there is a clear and unmistakable national consensus against the imposition of the death penalty on persons with mental retardation, and (2) the American people oppose the execution of individuals with mental retardation because the practice offends our shared moral values. (emphasis mine.)

So once again I am the sole hold out to national consensus. Okay. If I am to grant that such a national consensus does exist-- which it most obviously does not-- it is not in small measure due to misunderstanding what mental retardation is: it isn't Down's syndrome. It isn't a guest spot on the Howard Stern Show, it isn't finger paints and a baseball cap at age 30 moaning, "I wanna eat tato chips!"

If it was this, I'd agree a consensus might even be close to unanimous. Ironically, such a consensus would be irrelevant as such individuals don't commit capital offenses.

But this is not what mentally retarded is. Atkins, the above defendant, was determined by the defense expert to be MR because of an IQ of 59. With this IQ, he was able to get drunk and smoke pot (which, FYI, does not diminish responsibility,) drive a car (which he was licensed to do), kidnap and drag his victim to an ATM to force him to withdraw $200, then drive him to an isolated spot and shoot him 8 times-- not to mention be competent to stand trial, cooperate in court and with his attorney, etc. He was also able to pull of 16 other felonies in his life. An IQ of 59 allows reading at a 6th grade level-- comic books are 4th grade and Time Magazine is 9th grade.

But that was Atkins. A diagnosis of MR is an IQ less than 70. Can someone with an IQ of 70 appreciate that shooting your kidnapping/robbery victim in the chest 8 times and dumping him in an isolated location is really, really, wrong? From 1976-2002, 44 people with "mental retardation" have been executed; all but 2 had IQs at least 58.

So a categorical exemption for the mentally retarded might be sensible if someone could tell me exactly what mentally retarded means. Because the psychiatric definition quite obviously covers individuals well within competency standards. And that's the point.

Here's an example: if the exemption was for "Down's Syndrome" then this would be plausible, because a) we can reasonably agree how Down's impacts the defendant; b) we can identify it. But "retardation" means-- what? Mentally ill, as an exemption, is worse-- does depression count? Only psychosis? Does the presence of only a hallucination count, or do you have to have a thought disorder? "Schizophrenia?" What's that? The John Nash type, or the homeless crackhead type? How about borderline? Narcissism? If you can't be sure of what constitutes "mentally ill", how can you make a blanket exemption for it?

We can take this debate up a level, and observe that with every other psychiatric disorder that impacts on legal matters, the question for psychiatrists is simply, "what's his disorder?" or "how does the disorder impact this case?"-- we have an advisory capacity, leaving the ultimate decision of culpability up to the courts. In this way, we put some distance from the outcome. That's what expert testimony is all about. Fair enough. But now, with MR, the diagnosis automatically gets you out of execution. As long as the IQ test comes back 59, the sentence changes. Mental retardation is binary, apparently, and if you are fortunate enough to have it, you live-- regardless of how well you understood the wrongness of your actions, or how egregious were the crimes.

Which is ridiculous. There are practically no valid measures for any psychiatric illnesses-- everything is up for debate and interpretation. MR especially is a continuum disorder. Factors as trivial as which IQ test is used, or when it is taken, can affect the diagnosis. One study finds a 6 point increase using older tests vs. the newer version of the same test.

"Our findings imply that some borderline death row inmates or capital murder defendants who were not classified as mentally retarded in childhood because they took an older version of an IQ test might have qualified as retarded if they had taken a more recent test," Ceci says. "That's the difference between being sentenced to life imprisonment versus lethal injection."

But now the law has set an arbitrary and empty, binary cut off for execution. Psychiatrists now actually choose the sentence. Not inform the sentence-- choose it.

I'm fairly certain the APA didn't think about this when it filed its amicus brief. They never think these things through, because they believe they are an instrument of social change. But, like forced medication to render competent to be executed, psychiatrists have now boxed themselves into a corner. It is now solely up to them-- and their "tests"-- to decide who gets executed.

Consider the ethical dilemma for a forensic psychiatrist asked to evaluate for MR: given that the defendant can fake MR; and given that finding the defendant does not "have" MR--or suspecting that he is faking MR-- is exactly equivalent to sentencing him to death, can there be any other medically ethical outcome than finding they are MR? Think well. In other words, an answer is forced, an answer is created, simply by asking the question. The situation here is identical to the judge leaning over and asking, "Do me a favor and decide for me. Should I hang him or put him in prison?" Um, well, gee, it's up to me? um, since you asked...

I know, doctors are going to inwardly smile, pat themselves on the back for their cleverness; after all, the goal is to abolish the death penalty for everyone, one group at a time. And I am sure there are organizations who will actively, openly, exploit this loophole.

Notwithstanding the laudability of this goal, this isn't about the death penalty, it's about who decides the death penalty.

Just remember, when society allows psychiatrists to decide who lives or dies, then psychiatrists will also decide who dies or lives. I want everyone on the planet to take a very deep breath, and think about this.

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Score: 2 (2 votes cast)

Further Thoughts on Competency To Be Executed

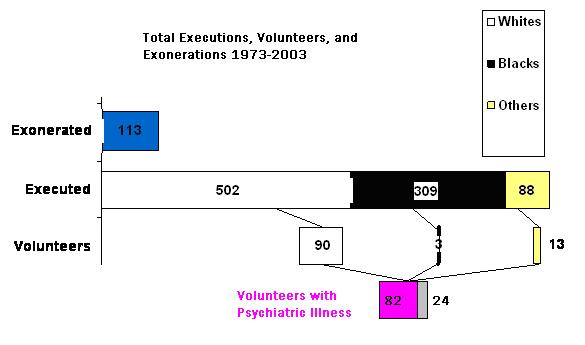

I took the data in the paper "Killing the Willing: "Volunteers," Suicide and Competency" and drew this chart.

The paper is fascinating. It observes that although blacks are disproportionately represented in executions versus the general population, volunteers to be execute-- i.e. people who waived their appeals-- are overwhelmingly white, male, and have psychiatric illnesses, especially borderline, depression, and psychoses (and an additional 10% have substance abuse)-- which is basically your demographic for suicide attempts. 30% also had prior suicide attempts.

So the author asks: if there is no such right to assisted suicide (indeed, any suicide at all), can there ever be a waiver of the appeal in capital cases? Even if the defendant is competent, if suicide is a motivation, the author writes, "their decisions should not, indeed must not, be honored, at least so long

assisted suicide is not available to other persons in the jurisdiction."

The counter argument, of course, is that competency is a legal matter, and the person's motivations beyond that are irrelevant. For example, if a guy is sentenced to prison and wants to go, he still goes.

McClesky v. Kemp (1987) attempted to abolish the death penalty under the argument that executions were influenced by racial discrimination. This was rejected. But Atkins v. Virginia (2002) did abolish the executions of the mentally retarded. Consequently, abolition of the death penalty, or at least a drastic curtailing of it, is more likely to occur along lines of competency and mental state, rather than any appeal to morality, race, or class.

I thought I knew how I felt about this issue, and now I am not so sure. But before anyone forms their opinion, I would strongly urge everyone to read the dissent by Scalia in the Atkins case. It should be required reading for every psychiatrist, whether you agree with him or not.

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Competency to Be Executed

If society has determined that a right to commit suicide does not exist, can a convict sentenced to death waive his appeal?

Continue reading:

"Competency to Be Executed" ››

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Score: 4 (4 votes cast)

Competency To Commit Suicide?

Continue reading:

"Competency To Commit Suicide?" ››

Score: 3 (5 votes cast)

Score: 3 (5 votes cast)

Not Competent To Make Medical Decisions?

As a forensic psychiatrist, I am often called to evaluate someone for their "competency"-- to make medical decisions, to make financial decisions, to stand trial, and (theoretically) even to be executed.

In these various consults, the basic question is this: are they so impaired, that they don't understand the relevant issues and can't make rational decisions?

Many psychiatrists find this complicated and time consuming work, because they focus on the nuances of the patient's symptomatology and illness. They try to get extensive past histories, corroborating information, etc, etc. All this is important, but they miss the forest for the trees.

Now this is, of course, only my opinion. But it's important that you hear this opinion, because I am, apparently, the only person who has it, so you won't hear it anywhere else.

The truth to competency evaluations is this: the patient is the least important factor.

Continue reading:

"Not Competent To Make Medical Decisions?" ››

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

How to Write A Suicide Note

I'll write this for the ER psychiatrist seeing acute cases, but the strategy applies to all types of psychiatry. Always keep in mind what is the purpose of the note, and who will actually be reading it.

Continue reading:

"How to Write A Suicide Note" ››

Score: 14 (20 votes cast)

Score: 14 (20 votes cast)

$51M Vioxx Verdict Overturned

Judge Fallon decides that the jury's $50M award is a bit much for a heart attack in which the guy is still alive and well. He leaves in place $1M punitive damage award. (The $50M was compensatory damage.)

I also refer you to the PointofLaw blog, in which is observed the inconsistency of the jury's verdict: no, they aren't strictly liable for failing to warn about and causing the MI; and yes, they were negligent in failing to warn and causing the MI. How can you be negligent if you weren't liable?

Liable=responsible

negligent= "careless in not fulfilling responsibility" (from law.com). There was a duty toward the person AND you didn't do what a reasonable person would have done AND what you did actually caused the damage

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Vioxx

Merck's previous win in the Vioxx suit gets thrown out because the judge was concerned about the new criticism of the NEJM study.

What happened is an idiot's guide to forensic computing. Greg Curfman, executive editor of NEJM, was going to give a deposition in the trial of Frederick Humeston, an Idaho postal worker (or he was just curious about the data after Vioxx was pulled-- depends on which story you read) and so pulled the manuscript. Back in 2000 you'd submit a paper copy and a disk; NEJM says they worked off paper, so the first time they looked at the disk was Oct 5, 2004 (days after Vioxx was withdrawn.)

Here's the fishy part: on the disk was a table called "CV events," which was blank.

Time stamps in the software indicated that the table was deleted two days before the manuscript was submitted to The New England Journal on May 18, 2000. "When you hover the cursor over the editing changes, the identity of the editor pops up, and it just says 'Merck,'" Curfman says.

What's so terribly misleading about this and NEJM's "Expression of Concern" is this statement:

We determined from a computer diskette that some of these data were deleted from the VIGOR manuscript two days before it was initially submitted to the Journal on May 18, 2000.

This isn't true. First, the missing MIs were never in the table to begin with. Second, the table was deleted, but the data itself was still in the paper.

Now it is obvious the study attempts to minmize the thromboembolic risks. What do you expect from an academic study? Let me assure you-- if you think drug reps are biased, go find yourself a professor. So I acknowledge the criticism that the study is misleading. But.

But it's the social policy angle that gets me, the moralistic high ground of journal editors who are far worse than study authors. The gateway to hell is peer reviewed.

The article says Curfman was deposed by plaintiff's lawyers. Was Curfman paid by them? It doesn't mean he's biased, but if you have to disclose Pharma sponsorship, don't you think you should disclose lawyer sponsorship? (and I am looking to find out if he was indeed paid.)

As I have absolutely no interest whatsoever in the actual outcome of these trials-- my interest is really about how doctors butcher science and promote themselves to senators-- but, we should take a look at what this revelatory missing data says.

What they found was that with the inclusion of the missing data, the rate of heart attacks would have been 5 times greater than naproxen, not 4 times. 0.5% vs. 0.1%.

Just to put this in perspective, of course, you should know that the missing data was three more heart attacks, raising the number of patients with MI from 17 to 20 (out of 4000+ patients), vs. 4 in tha naproxen group.

BTW, "five times" and "four times" may sound like big differences, but they do not even approach statistical significance in this study.

BTW, strokes were the same in both groups. Not that anyone cares, of course.

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

Score: 0 (0 votes cast)

For more articles check out the Archives Web page ››